Three Things To Read This Week

1. More Cities Embedding Mental Health Experts Into 911 Dispatch Centers.

In Phoenix, Arizona, “911 Callers … Will Now Be Asked About Mental Health.” For KJZZ, Matthew Casey reports on the new mental health program launched at Phoenix’s 911 emergency dispatch center that “instead of just asking if emergency callers need police officers or fire fighters, Phoenix 911 dispatchers are now also asking if people need help with behavioral health… [with] the goal to reduce unnecessary responses by police and fire.” Local leaders explained that if a caller needs mental health service, now “they’re transferred to a special dispatcher, who then sends out staff from the Community Assistance Program, which includes mental health units and crisis response teams.” Phoenix’s approach follows the model pioneered in Austin, Texas that Safer Cities has spotlighted—when you call 911 in Austin, a dispatcher will ask you: “Do you need fire, EMS, police”—or, the fourth option—“mental health.” Then, they determine the appropriate responder team, based on the needs of the caller. DC Ernst, who oversees the Community Assistance Program in the city, explained in an announcement about the 911 policy shift that “the goal is to ensure the right help is sent to the right calls … ‘this enhancement … ensures residents receive the most effective response available for their situation.”

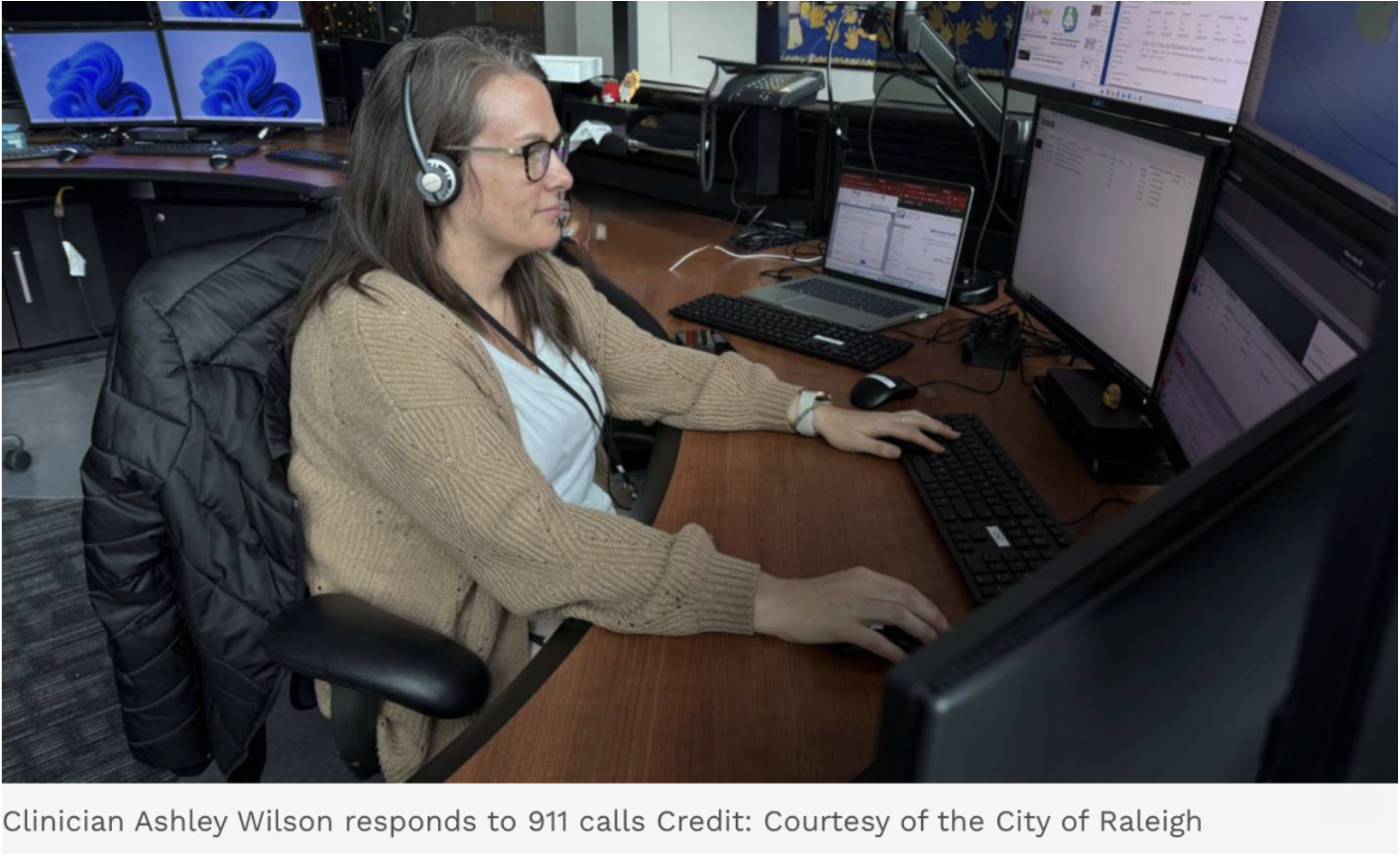

In Raleigh, North Carolina, A “Team Of Licensed Mental Health Clinicians [Is Now] Embedded Within The 911 Call Center” To Help Determine the Best Responder. For Indy Week, Chloe Courtney Bohl reports on the new pilot program which places “a team of licensed mental health clinicians embedded within the 911 call center who are trained to de-escalate mental and behavioral health crises and connect people with long-term support… assessing whether police officers are best equipped to respond to the situation or if a mental health professional should intervene instead.” Indy spoke with Dominick Nutter, the city’s Emergency Communications Director, as well as Michele Mallette, the city’s Chief of Staff, who championed this shift. The full interview is worth your time but here are some key learnings from the pair:

Why Add Mental Health Clinicians To 911? “One of our former police chiefs… recognized that there was a growing need—not just from community concern but from a police resource standpoint—for an alternative for the community that was experiencing mental health crises. We decided we would embark on developing our crisis call diversion line… as we divert calls over to the clinicians, it helps with our improved response time. If [police] responders aren’t going to those calls, they can focus on other calls where the public needs them, and it’s going to reduce the time it takes us to get there.”

How Does It Work At The Call Center? “A 911 call comes in and we have our standard case entry questions… as they start explaining the situation, our team will decide if it’s something that is appropriate for [police, fire or mental health response]... The big thing is, does the person have a weapon and is there any danger? In that case, then [mental health response] wouldn’t be appropriate. If it’s something that’s appropriate for [mental health response], then the call is transferred to a counselor. One of our telecommunicators will talk to the counselor first so the counselor is aware of the situation, and then they will bring in the caller…. Often we are helping people access resources like behavioral health urgent care, crisis assessment, or mobile crisis, a service that comes to people’s homes and helps them figure out the best next steps for them, while assessing that it’s a safe step.”

2. Three Studies Show Promise That Mobile Crisis Response Teams Can Reduce Strain On Police, Jails, And Hospitals While Building Trust.

Mobile Crisis Teams Reduce Arrests, Strain On Jails And Hospitals. In a recent review of multiple studies evaluating mobile crisis units, published in BMC Health Services Research, researchers found that “mobile crisis proved to be the only intervention that led to significantly lower incidence of arrest in the year following [an] initial crisis,” compared against co-responder units and officer-based response. They conclude that mobile crisis team treatment “reduces individuals’ likelihood of arrest… in the period after treatment compared to controls similarly at risk for these outcomes,” and emphasize that mobile crisis team treatment reduces jail admissions as well as emergency room admissions.

The “True Unmet Need” For Behavioral Crisis Response Is Far Greater Than Previously Thought. Analyzing computer-assisted dispatch data from 15 U.S. police departments, researchers in a recently published pre-print study found that with “police officers having long been the default, primary responders to mental and substance use related incidents in the United States… some U.S. cities may see up to 20% of police dispatch time spent on behavioral health” calls for service. Based on these estimates, the study concludes that “the true unmet need for alternative crisis response in U.S. cities is far greater than previously thought,” and that these findings “may offer a reasonable guide for municipalities that are considering implementing an alternative crisis response service.”

Portland Street Response Team Increased Trust In City’s Emergency Response Among Homeless. In a recent study published in the Journal of Prevention and Intervention, researchers examined Portland Street Response, the city’s mobile crisis response team, and its impact on trust in the homeless community as it began to respond to homelessness-related calls for service. Researchers found that many in the homeless community initially reported feeling “unsafe calling 911,” citing concerns about what response might arrive and whether help would meet their needs. But as awareness grew that Portland Street Response was an available responder option, trust increased: the share of unhoused respondents who reported feeling unsafe calling 911 “dropped from 57.9%… to 44.9% after the program had been active for two years.” Clients of Portland Street Response consistently described feeling treated “with compassion and dignity,” saying responders “treated us like humans,” and emphasizing the reassurance of having a clearly defined alternative response option: “I don’t worry anymore. I can say I need Portland Street Response.”

3. Momentum For Crisis Stabilization Centers Across The Country.

In Prince William County, Virginia, New Crisis Stabilization Center “Shows Early Success.” As the county details in their announcement, the new center, which opened in October, “is already demonstrating strong early results in supporting individuals experiencing behavioral health crises and reducing reliance on inpatient psychiatric hospitalization… [with] out-of-area [hospital] placements dropping from 43 percent to just four percent.” The center’s medical staff provide a range of mental health services and treatment to patients, who can arrive via law enforcement drop off or hospital transfers, through an “on-site Crisis Stabilization Unit for individuals requiring more intensive, short-term care… [as well as] outpatient and community-based services” for people with less acute symptoms.

In Wayne County, Pennsylvania, New 24/7 Crisis Stabilization Center Opens, “Taking Pressure Off” Of Local Emergency Rooms. For WVIA, Lydia McFarlane reports on the Northeast Regional Crisis Stabilization Center, which opened its doors at the end of 2025, that local officials say is “already making a difference” in the health and safety of the community. The center is “staffed 24/7 and anyone can be treated there, regardless of age or where they live.” It features a residential treatment program “where individuals can stay for up to five days”—a “first of its kind” service in the county. Local leaders told the news station that the new facility is “taking pressure off Wayne Memorial Hospital.” John Nebzydoski, the county's behavioral health director, explained how the county views the facility’s role in the public safety infrastructure: "We're comparing this to an urgent care… If you're in mental health crisis, you're not bleeding, you're in reasonably good physical health, please come here.”

In Hennepin County, Minnesota, A New Youth Crisis Stabilization Center Is Serving Kids “With Complex Mental Health Needs” Who Would “Otherwise End Up In An ER Or Detention Center.” For The Star Tribune, Eleanor Hildebrandt reports on the county’s new crisis stabilization center for kids, that just opened in December, providing treatment for youth “with complex mental and behavioral health needs who have long been stuck between [being sent to] emergency rooms and juvenile detention,” but now can receive mental health care at the facility instead “for up to 45 days.” The center, staffed with trained medical professionals, provides kids in crisis with “a calm place to stay for a few weeks and get help while figuring out what to do next.” Its design, which came about through consultation with mental health care professionals and “feedback from families and youth” has a “a familial vibe to the space, including a dining room area… [and] every room has a personal bathroom and desk.” Kids can receive “multiple types of therapy while there… [and] will also be taught by a Minneapolis Public Schools teacher while they stay."