Three Things To Read This Week

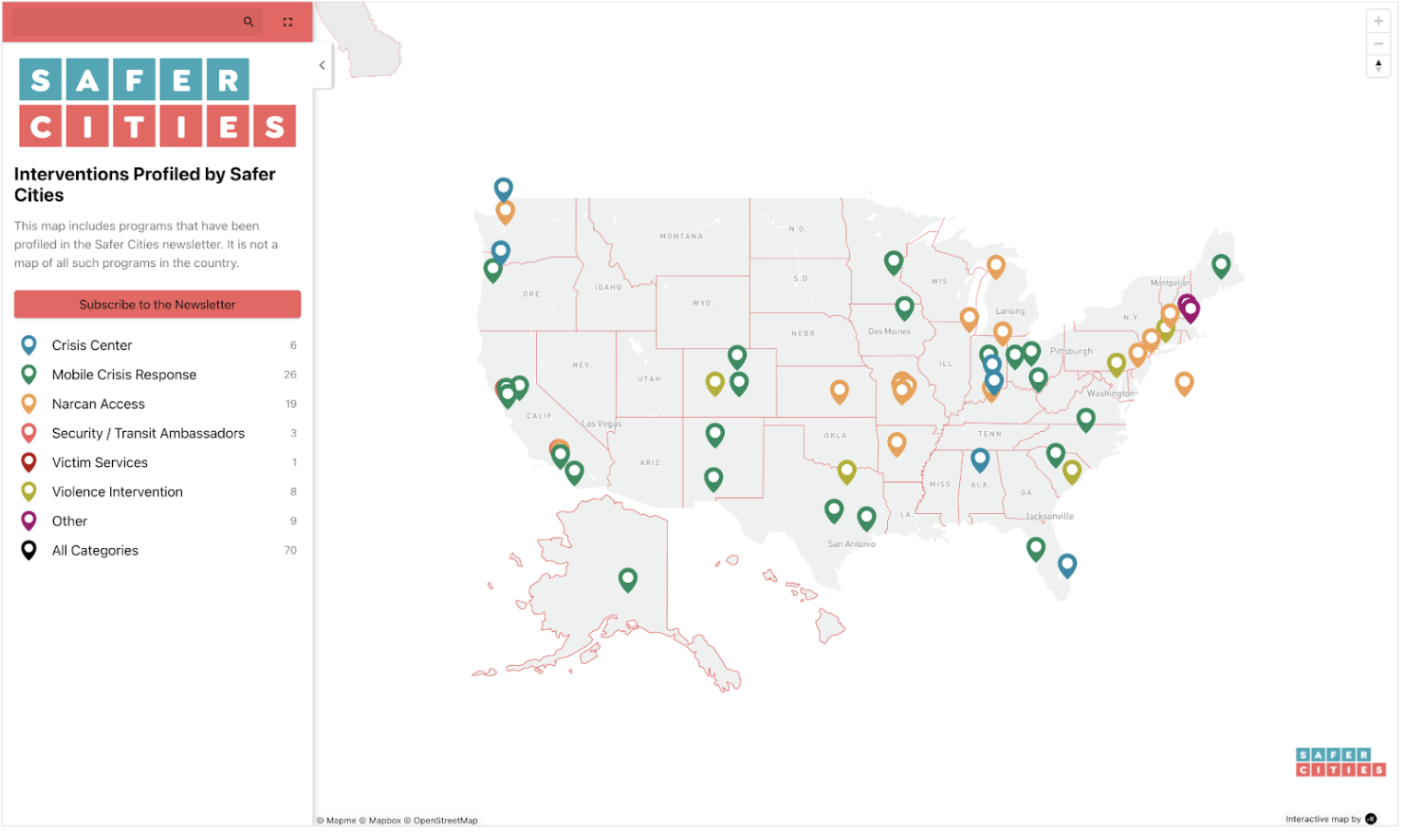

1. Introducing The Safer Cities Coverage Map.

As cities across the country build out a new public safety infrastructure, the good—and bad—news is that there’s so much activity that it’s hard to keep track. That’s why Safer Cities created this coverage map, which curates many of the innovative programs that we’ve covered from crisis stabilization to mobile crisis response times, from Narcan access to trauma recovery centers.

We hope the map will prove to be a useful tool for readers. In the meantime, we’d appreciate suggestions for how to improve this resource to make it more helpful—email us at: matt@safercitiesresearch.com.

2. NYU Policing Project Report: Focus “Armed Police Officers” On “Really Dangerous Situations” And “High Stakes Cases.”

Last week, Safer Cities featured the first of three editions highlighting an important aspect of New York University Law School’s Policing Project’s newly published report on Denver’s mobile crisis response program, STAR, or “Support Team Assisted Response”. The report includes insights from interviews with 911 dispatchers, police officials, STAR’s own clinicians, and “residents of Denver’s communities most affected by policing and other first response practices.”

This week’s edition dives into a thorny question: If Denver STAR is so effective, then why are 911 dispatchers not dispatching STAR to most STAR eligible calls?

The NYU researchers found that the degree to which 911 dispatchers utilize STAR depends on the call type. For example, “welfare checks received a STAR response nearly half of the time … [while calls related to] encampments and suicides received a STAR response much less frequently.”

Here’s what 911 call dispatchers told the researchers about when and why they do (or do not) dispatch STAR:

STAR Is So New That Sometimes Dispatchers Simply Forget To Dispatch Them. Researchers found that “911 operators and front-line workers [have] overwhelming appreciation for STAR [but also, at times] … forget to utilize this new ‘fourth option.’” One 911 dispatcher explained the challenge to the researchers:

“I don’t think there’s a lot of hesitancy in terms of, ‘Oh gosh, I don’t want to add STAR to this,’ it’s more of a, ‘Oops, I forgot,’ [because] it’s just newer, so it takes time to adjust to everything. But I think as the STAR program expands in Denver, that’ll kind of resolve itself in time.”

To combat this “lack of awareness and understanding of what precisely the clinicians and medics in the STAR van can do,” researchers report that STAR “program managers are working to educate dispatchers and call takers on the skills STAR responders have in order to make them more comfortable with utilizing the program.”

Dispatchers Remain Hesitant To Send STAR Team Members Into Harm’s Way. Researchers found, for some calls, there was “significant hesitation from dispatchers to send unarmed responders out in the field.” Here’s one of the 911 dispatchers making the point that dispatchers both don’t want to be held liable if a STAR team member is hurt and don’t want to be morally responsible for inadvertently getting someone hurt:

“For me, in the chair, if STAR can’t protect themselves, I’m not sending them by themselves… It’s a liability that... then falls on us, as the dispatcher. ‘Why did you send them there? Now they’ve gotten hurt. Now it’s your fault’ … You really need to go with your gut for what’s risky, that you never want someone to get hurt.”

Due to this fear, the researchers detail that during their interview with this dispatcher, she “shared that on intoxication calls—that, according to protocol, STAR technically can handle alone—she always wants to add police as a cover as extra precaution. She also adds police cover to all suicidal calls, which, like intoxication calls, are one of the seven call types that are deemed STAR-eligible. She explained that, in her mind, preserving the safety of first responders is the primary concern of 911 operators.”

This fear over sending STAR is not shared by STAR team members. Here’s a quote from a Denver STAR responder making the point:

“I had a dispatcher the other day who was like ‘God, I just hate sending STAR to an apartment or house because it’s … like you’re going in and all this stuff could happen.’ I’m like, ‘We’ve delivered groceries and medications and picked people up. We’re used to going into people’s homes. We’re used to meeting people in alleys. We’re used to meeting people in parks.’ Send them. We got this. You have our back. You know where we are. We’ll call for help if we need it.”

The NYU researchers explain that this is a widespread sentiment among STAR responders: “STAR clinicians told us that they feel very comfortable going inside apartments and houses with individuals in crisis largely because they have done so many times in previous job positions.”

3. University Police Chief Says Campus Mobile Crisis Response Proves “Commitment To The Well-Being And Mental Health Of Its Students, Faculty And Staff.”

The University of California–Irvine partnered with Be Well OC to launch a new mobile crisis response team on campus starting in the Fall semester.

The team, composed of two trained mental health crisis counselors, will respond to calls for service from both 911 and the UCI nonemergency dispatch with a goal to “offer direct mental health assistance and significantly reduce the need for police and emergency medical services in such scenarios.” UCI Police Chief Liz Griffin lauded the launch saying that it reaffirms the university’s “commitment to the well-being and mental health of its students, faculty and staff.”

UC-Irvine is just the latest of a growing number of universities, disproportionately located in California, that have begun to dispatch mental health experts to some calls for service on campus. Here are three examples:

California State University–Fullerton. For the Orange County Register, Lou Ponsi reports on the newly announced mobile crisis response team that “consists of unarmed, unsworn safety specialists partnering with licensed mental health professionals to respond to nonviolent crisis calls.” CSU-Fullerton Police Chief Anthony Frisbee told the newspaper that the model for the campus mobile crisis response team, which is a partnership between the university’s Counseling and Psychological Services Department and the campus police department, not only gets people in distress the help that they need, but also “frees up police officers to focus on prevention, intervention and responding to calls involving violence or criminal activity.”

University of California–Berkeley. For The Daily Californian, UC-Berkeley’s student newspaper, Lia Klebanov reports on the new “Campus Mobile Crisis Response” team, composed of EMTs and clinicians, which responds to mental health-related calls for service from university students, faculty, and staff. The team will also “reduce the number of calls that a uniformed officer needs to respond to,” Russ Ballati, senior project manager in the university vice chancellor’s office, told the newspaper. “It’s a huge benefit to everybody because UCPD doesn’t have the staff to be able to respond to these types of calls, nor do they have the experience to respond.”

University of Utah. For the campus news service, Benjamin Gleisser covers the university’s “Mental Health First Responders” team—composed of “a program manager, two licensed social workers, and two master’s candidates in social work who serve as interns”—which “supports students living in [university] residence halls experiencing a mental health crisis” seven days a week from 4 p.m. to 2 a.m. The key to the program, a partnership between Huntsman Mental Health Institute and the University Counseling Center, is that it centers “around mental health intervention, rather than a direct call for police intervention, which might increase any anguish the distressed student already feels,” Gleisser writes.