Three Things To Read This Week

1. Report: Harvard Examines How Crisis Responder Teams Are Operating Around The Country.

Published by the Harvard Kennedy School Government Performance Lab, the new landscape analysis examines 911 and program data from nine crisis response teams in operation around the country. Using de-identified dispatch and operational data, the report examines how the teams are structured, dispatched, and integrated into local emergency systems. Across the report, researchers identify “findings on emerging trends in program model variation” and “on early insights into performance.”

The nine programs examined include some of the most lauded responder programs around the country that Safer Cities has been covering for years, including: Durham’s Holistic Empathetic Assistance Response Team (HEART), Harris County’s Holistic Assistance Response Team (HART), Los Angeles’s Unarmed Model of Crisis Response, Madison’s Community Alternative Response Emergency Services (CARES), Minneapolis’s Behavioral Crisis Response (BCR), New Orleans’s Mobile Crisis Intervention Unit, Portland’s Street Response (PSR), and San Francisco’s Homeless Engagement Assistance Response Team (HEART) and Street Crisis Response Team (SCRT). The full report is worth your time, but here are some of the emerging trends and learnings researchers highlighted:

Embedding Into 911 Systems: “The majority of incidents [that these crisis teams] respond to come directly from 911 dispatch” … and crisis responder teams were the “primary and only responder team” in 79 percent of incidents.

They Resolve Most Calls Without Assistance From Law Enforcement, EMS: “The majority of 911 incidents CRTs respond to are handled alone, without additional responder teams on scene.” When dispatched as primary response, CRTs are “responding to, and resolving, 95 percent of incidents on scene,” and they “rarely request back up while resolving 911 incidents as a primary response.”

Interdisciplinary Teams Can Handle Wider Range Of Calls For Service: “CRTs in our sample are mostly interdisciplinary, unarmed teams (mental/behavioral health, crisis, medical, and people with lived experience)” and they are “taking a wide range of non-violent 911 calls, not just mental health — including welfare checks, trespassing, and social service needs” with “incidents related to mental health and welfare checks comprising the largest percentage of incidents.”

Teams Provide Immediate Response As Well As Connection To Stabilizing Services After Acute Crises: “When dispatched to 911 incidents, CRTs provide immediate on-scene response,” and “provide connections to voluntary services including case management and care coordination, shelter/housing resources, and medical services.”

Spotlight On Some Of The Teams From The Harvard Report:

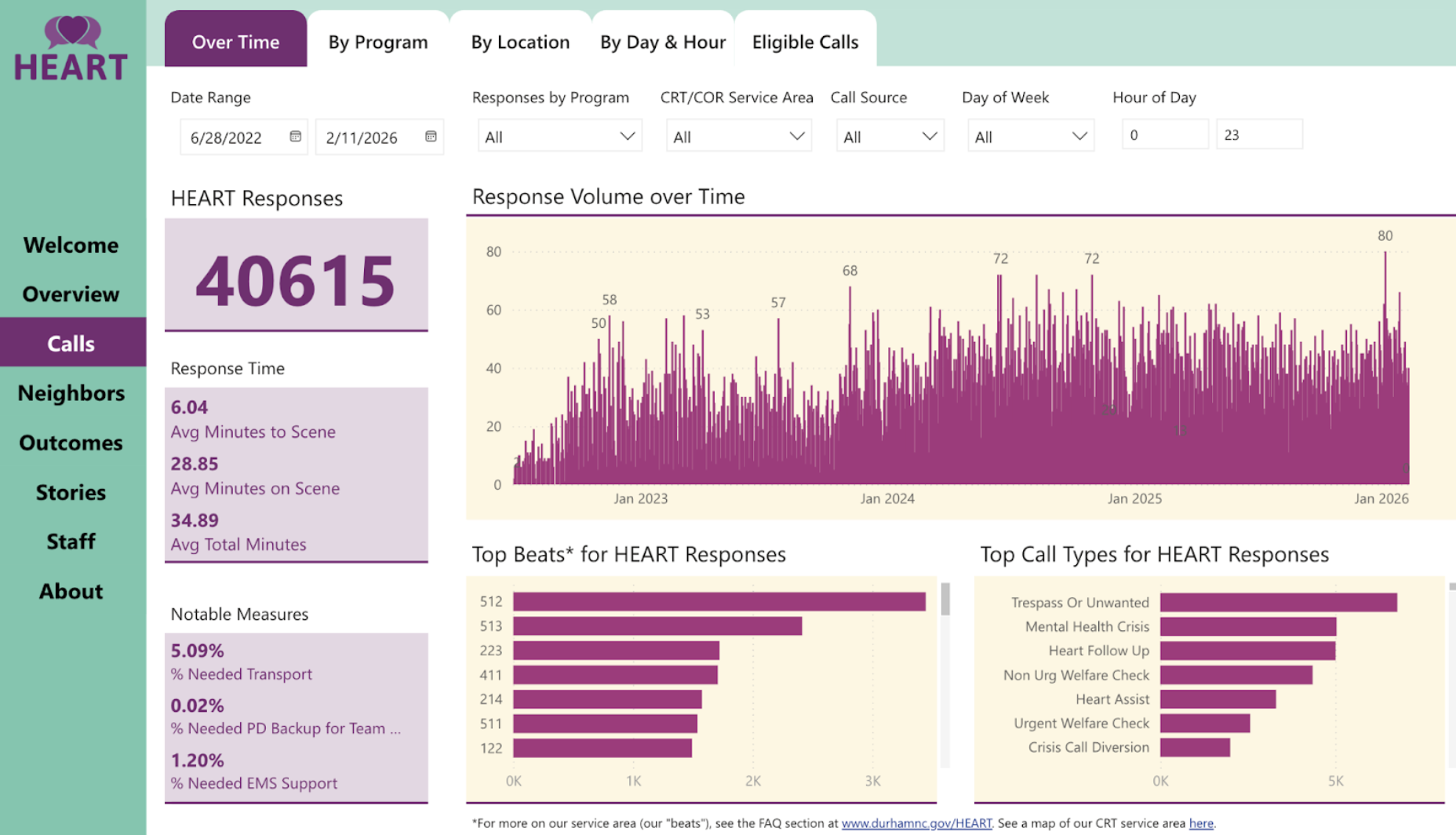

Durham’s HEART Has Responded To More Than 40,000 Emergency Calls, Has “Alleviated Strain On The Police Department.” Since its launch, Durham’s Holistic Empathetic Assistance Response Team, or HEART, has handled more than 40,000 calls for service, according to the latest city data tracking the program. For WRAL, Lora Lavigne reported that HEART’s work “helped avert thousands of crises and alleviated a strain on the police department.” City leaders expanded the team last year, including “17 new full-time HEART staff members… [and] expanded coverage during the day as the city plans to eventually operate 24/7,” CBS17 reported. Durham Police Chief Patrice Andrews recently said that the Durham Police Department “continues to be fully supportive of the HEART Program… because it enables us to focus on more appropriate law enforcement needs throughout our community.”

Portland Expanded Its Street Response Team Into A Community Safety-Style Department—“An Equal Part Of The City's Public Safety System, Alongside Police And Fire.” For KGW8, Portland’s NBC News affiliate, Blair Best reported on Portland’s City Council passing a resolution to expand the Portland Street Response team last summer, “formally establishing [it] as an equal branch of the city's public safety system… to take some of the burden off first responders like police and firefighters.” The department, which has been responding to mental health calls since 2021 when it first launched, will now be expanding its ranks and reach to 24/7 service across the city. Its staff receives the full “designation as first responders, with all the associated [employment] benefits,” and the team “will also get direct dispatch through 911.” A spokesperson for the city’s police department told the news channel that Portland Street Response “are a valuable piece of Portland's public safety system, and we work with them regularly. We hear on the radio all the time officers asking for PSR, and it gives those officers another option for someone who doesn't need police assistance but needs help in other ways … We're happy to do our part and welcome an expansion of their program.”

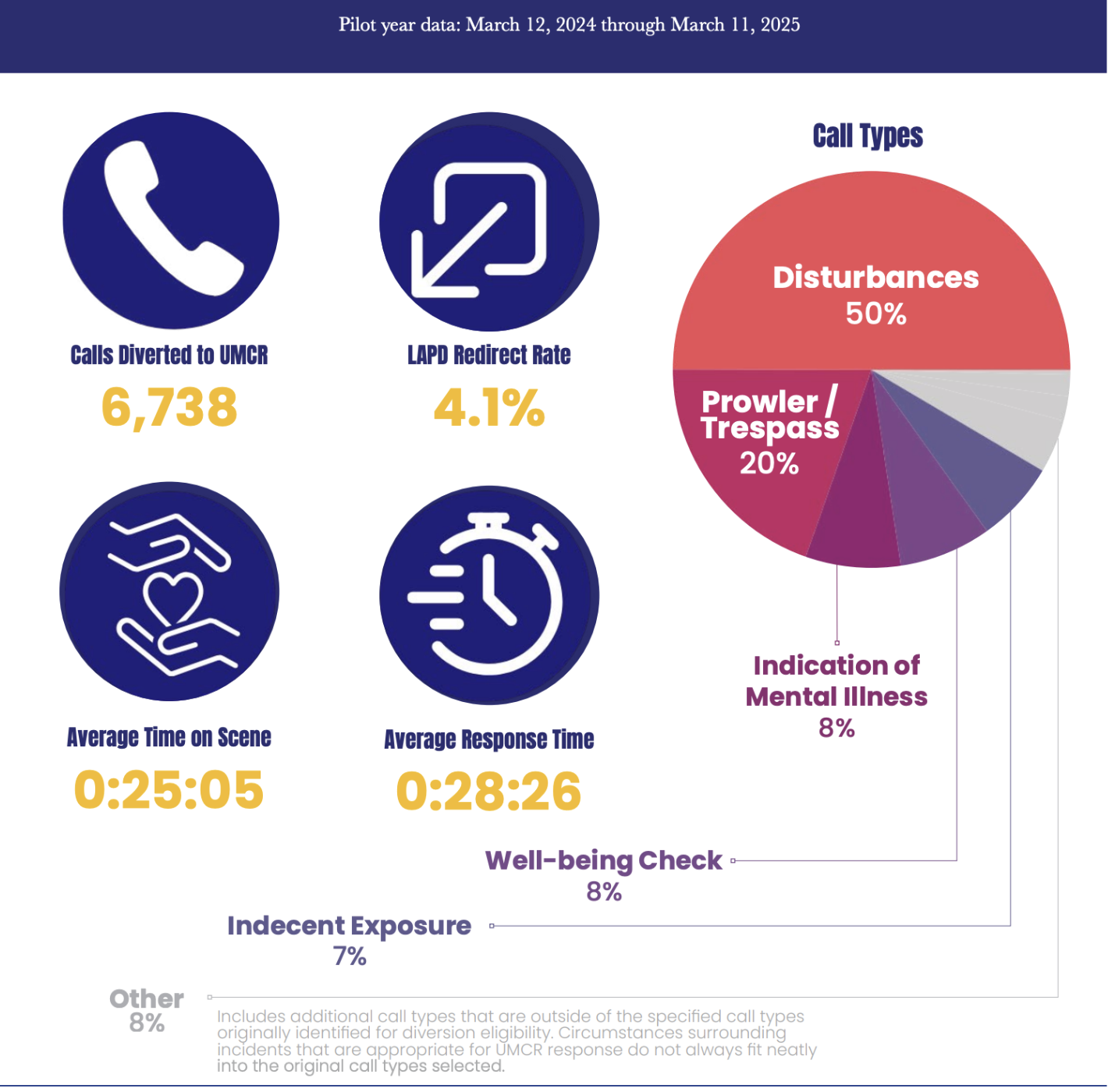

In First Year Pilot, Los Angeles UMCR Team Responded To Nearly 7,000 Calls, “Saved LAPD Officers’ Time … [So They Could] Respond To Higher Risk Calls For Service.” That’s one of the key takeaways from a report published by the L.A. City Administrator’s Office, which examined the calls for service, response times, and resources saved by the UMCR crisis responders’ pilot in the city. The responders, “provide 24/7 mobile crisis responses to appropriate and eligible calls for service… related to mental health crises, substance abuse, welfare checks, and indecent exposure.” The city found that UMCR responder teams “are highly efficient, which is crucial for mitigating the impact of a crisis… not just responding quickly but also taking the time to evaluate the situation properly and plan for any necessary follow-up…. [an] approach [that] ensures that any immediate needs of the person in crisis are met while also addressing long-term support.” In their first year, the team responded to 6,738 calls for service and allowed for “6900+ hours [of law enforcement] patrol time saved.”

2. Study: Longer Engagement In Boston’s Hospital Violence Program Linked To Lower Future Violence.

In a new study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, researchers from Boston University School of Public Health examined Boston Medical Center’s hospital-based violence intervention program (called the Violence Intervention Advocacy Program) and evaluated whether it reduced future violence among “young adults aged 16 to 34 years who survived a shooting or stabbing.” The authors used a “target trial emulation using observational data,” comparing two treatment strategies: “any treatment”—engaging “within 1 month of injury”—and “sustained treatment”—initiating within 1 month and “engaging more than 4 of the first 8 weeks” post-hospitalization. Researchers tracked a combined outcome—“violent reinjury or violence perpetration”—using “hospital and police data” at 1, 2, and 3 years after the index injury.

Notably, the researchers found that patients who received “sustained treatment” were linked to “considerably lower cumulative incidence” of violence at 1, 2, and 3 years—with risk reductions exceeding 50% at two- and three-year follow-up. Other key findings:

Sustained Engagement Was Associated With Much Lower Risk. In the “sustained engagement analysis,” treatment was linked to “considerably lower cumulative incidence … 6.4% … at 3 years” versus “14.3%” in the control strategy … with “risk reductions … 55.3% … at 3 years.”

Dosage Mattered. The authors conclude that HVIPs can improve long-term violence outcomes, but that “these effects seem to require intensive participant engagement.” That’s in contrast to the “any-treatment analysis,” where researchers found that “estimated cumulative incidence was roughly equal between the treatment and control strategies.”

Models Vary. The findings affirm the “violence prevention potential of HVIPs,” but researchers caution that because “there is no single, agreed-upon package of services for all HVIPs,” “it is unknown how our results may generalize to other HVIPs.”

Two More Hospital-Based Violence Intervention Programs Showing Promise:

In Virginia, Hospital-Based Violence Intervention Programs Across The State See “A Sharp Decline In Re-Injury Rates.” For The Virginia Mercury, Charlotte Rene Woods reports that the 12 HVIPs across the state, which “provide wraparound services… [to] victims of violence” are receiving a funding boost of $8.5 million from the state to continue their vital work. Since 2019, the newspaper notes, “more than 8,000 victims of violence have been served” by HVIPs across the state, which has produced “over $82 million in health care costs avoided due to preventing and reducing re-injury rates,” nearly half of that “estimated to be direct savings to the state.” A recent report from the American Hospital Association estimated that the total cost of violence to U.S. hospitals was roughly $18 billion annually. Moreover, the state’s Hospital and Healthcare Association, which oversees the hospitals providing violence intervention programming, announced that the effort has “resulted in a sharp decline in re-injury rates—the national average is 40 percent, compared to 3 percent for HVIP patients” in the state.

In Georgia, Grady Memorial Hospital’s Interrupting Violence In Youth and Young Adults Project Sees Reinjury Rate “Far Below The National Standard.” Emory University School of Medicine, which helps to oversee the IVVY program that runs out of the Level 1 Trauma Center at Grady Memorial Hospital, recently announced that the program is making a significant impact in reducing violence in the region, with “less than two percent of patients treated in coordination with the IVVY Project have returned with a gunshot wound—a reinjury rate far below the national standard of 30-40 percent.”

A recent paper published in Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open by some of the physicians working in the IVVY program outlined the hospital-based violence program’s novel “three-pronged continuum of care model” called the “Bedside, Clinic, Community” model, which extends violence intervention beyond the hospital stay. Its three pillars include:“Bedside” care, where violence intervention specialists meet patients at the hospital bedside during the acute treatment phase, “providing immediate care to victims of violence at the time of injury” ensuring that they receive “medical treatment and psychological support” while creating “a seamless transition to ongoing wraparound services” in the later phases of treatment.

A multidisciplinary “Clinic,” a “one-stop shop” that combines ongoing medical care beyond the acute treatment phase as well as social services, including “physicians, advanced practice providers, wound care specialists, mental health experts, a social worker…” The clinic serves as a “critical bridge between immediate bedside care and long-term community resources.”

A “Community” partnership that connects patients to organizations for ongoing wraparound supports addressing “mental health services,” “education,” “employment,” “financial,” and “legal aid,” and broader housing, transportation, and food security programs.

3. Report: Expanding Crisis Response Requires Building A New Behavioral Health Workforce.

In a new report published in the journal Psychiatric Services, researchers examine the rapid expansion of mobile crisis response systems across the country. Various investments have accelerated the expansion of the “third branch of public safety,” co-equal to police and fire, but the authors argue these efforts have been “hampered by limitations of the behavioral health workforce.” As crisis systems scale, workforce shortages persist, and new training academies are needed. The researchers propose that cities begin to build a new professional role—the “community behavioral health crisis responder”—grounded in “distinct values, competencies, and skills” to meet the growing demand. The full paper is worth reading, but here are some toplines:

Expansion Is Outpacing Workforce Capacity: “Behavioral health workforce shortages continue to present a challenge” to meet demand. Thirty-four states report shortages in mobile crisis staffing, “particularly social workers and other licensed providers, peers, and bilingual staff.”

Distinct Professional Role And Credentials: The authors argue that “a new professional role is needed that is rooted in unique competencies rather than attached to existing advanced academic credentials.” They urge states to “establish a [new] credential,” noting that “state behavioral health agencies as well as independent state and national credentialing agencies should establish and manage a credential” and that “some states are already developing their own certifications.”

Developing Training Infrastructure: The report recommends strengthening “the role of community colleges in crisis response workforce development,” arguing they are “well positioned to prepare trainees for credentialing” and can serve “as a pipeline for the local crisis response workforce.” The authors also call for regional “centers of excellence” to provide “standards, training, and technical assistance focused on crisis response workforce development.”

Related: Albuquerque Community Safety Department Has Its Own Academy Training The Next Gen Responder Workforce. The city announced its latest cohort of responder trainees at its academy last month, the department’s “12th academy class since ACS was established.” At the academy, trainees learn how to properly “address complex needs… including mental and behavioral health crises, homelessness, and substance use…. through comprehensive classroom instruction and hands-on training.” And new recruits are needed—the Community Safety Department has responded to a staggering 137,000 calls for service since its launch. ACS responders receive enhanced training through a partnership with Central New Mexico Community College, KRQE’s Scott Brown reports with a mixture of classroom learning, “hands-on” experience, and intensive “scenario–based” training.