Three Things To Read This Week

1. Mobile Crisis Response Teams Expanding—And Freeing Up Police And Fire Resources—Around The Country.

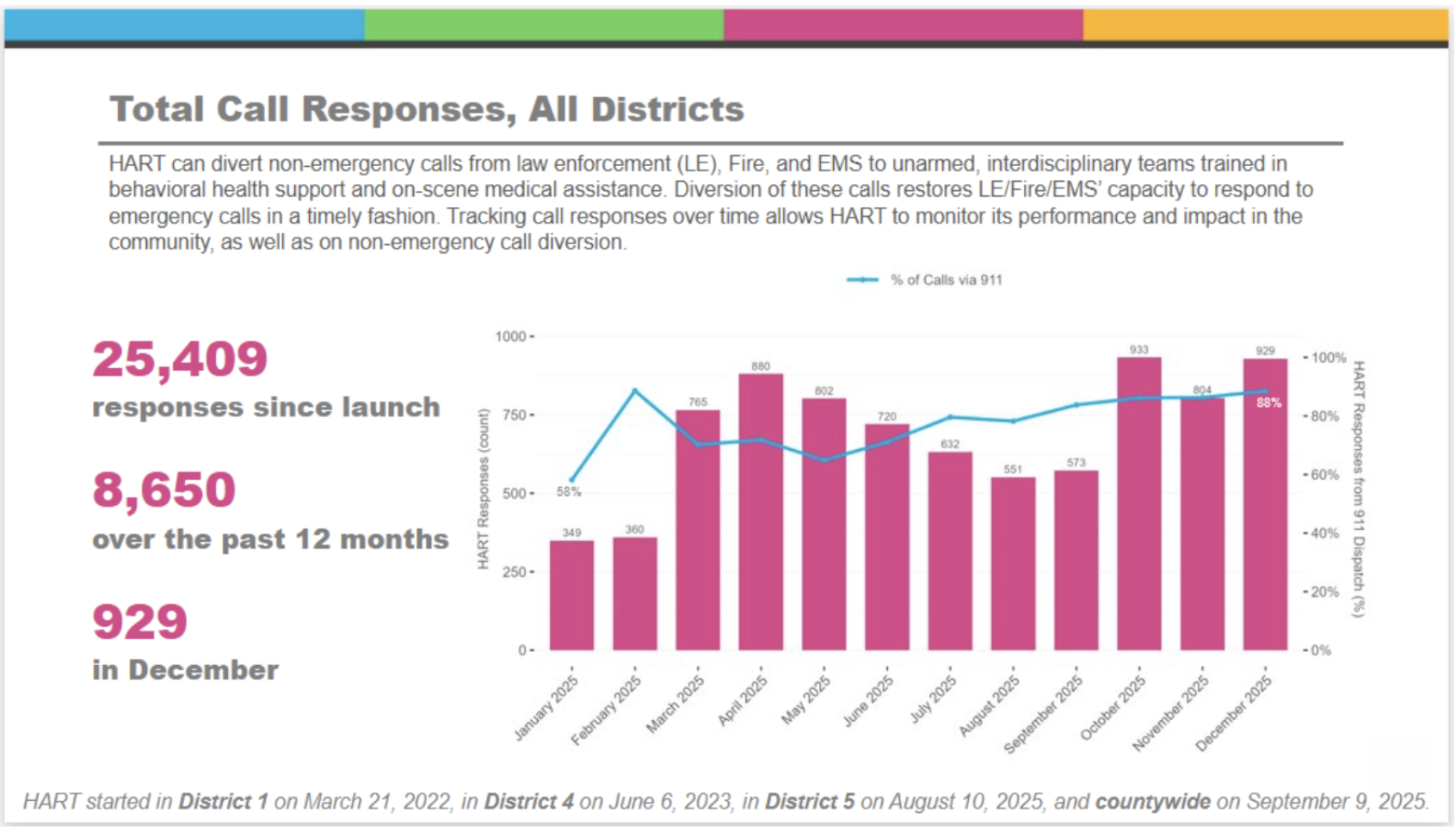

In Harris County, Texas, HART Mobile Crisis Responders Mark Major Milestone—Exceeding 25,000 Calls For Service. For Harris One, Harris County Commissioner Rodney Ellis announced last week that the county’s Holistic Assistance Response Team, or HART—a mobile crisis response team that “dispatches healthcare experts, crisis specialists, and other medical professionals to handle some 911 calls involving mental health, behavioral health, and homelessness”—surpassed 25,000 calls for service in December.

Commissioner Ellis, a long-standing champion of HART who first launched the team in his precinct, also noted that 88% of the team’s calls came directly from 911, “meaning the team is meaningfully reducing the burden on other emergency service providers in fire, EMS, and law enforcement, who would otherwise have taken these calls, and increasing [other first response] capacity in turn.” Here’s a look at the county’s data on the team:

The HART team first launched in 2022 as a pilot that responded to some emergency calls for service in Commissioner Ellis’s precinct. In the years since, the team has grown to “nearly 21 field-ready teams” who now respond to calls across the county, as well as a standalone hotline “offering a direct connection to the team” for residents in crisis. Here's what local leaders are saying about HART’s role in the public safety infrastructure in Harris County:

Harris County Sheriff’s Department Chief Mike Lee: Even in its first year in operation as a pilot, HART had already “‘freed up [hundreds of] hours of law enforcement time to respond to other calls… Officers still today find themselves in situations where they are nonstop dealing with calls in which the primary issue is poverty, lack of financial resources, substance abuse and addiction and mental illness. And I can tell you, police officers, although we are very proud of the training we have done, we're not the best equipped to handle that, and we acknowledge that that's not what our primary role should be,’” Chief Lee explained to the Houston Chronicle.

Harris County Precinct One Commissioner Rodney Ellis: “This is about which expert should respond to a 911 call, and in the past, we’ve asked too much of our friends in law enforcement when it comes to 911 calls for people experiencing a crisis or struggling with health issues and homelessness. When it's a robbery in progress, or a shooting, then obviously we need to send an armed sheriff’s deputy. But if we are talking about a person sleeping on a sidewalk, or a teenager who is suicidal and swallowed pills, then we need a behavioral health expert to respond. That’s the kind of crucial work that HART’s crisis intervention specialists do every day, and this is what it looks like to fully fund public safety in Harris County—we’ve got law enforcement, we’ve got mobile crisis response, and we’ve got community violence intervention. We are sending the right experts to solve the right problems.”

In Seattle, City Approves New “Permanent Expansion And Direct Dispatch” Of CARE Mobile Crisis Responder Team. Seattle announced last month that the Community Assisted Response and Engagement, or CARE—the city’s “third branch of public safety” co-equal to the city’s police and fire departments—will remove the team size cap from its previous contract. Now, the new contract that the mayor advanced “allows for permanent expansion and direct dispatch of the CARE department’s crisis responder teams.” The move, the mayor said, “marks a significant milestone for efforts to diversify emergency response options.” The expansion of the team will begin immediately, with the budget already approved to “double the number of CARE Community Crisis Responders… as well as supervisors, a new training manager, and additional equipment,” as well as “expanding the types of incidents [the team] can be dispatched to, and authorizes [the team] to be solo dispatched” to some 911 calls for service.

2. Cities Launching Mediation Responder Teams To Handle Non-Emergency 911 Calls For Service.

Local Leaders In Iowa City, Iowa, Launch Pilot Mediation Team To Respond To “Calls About Noise Complaints, Disputes Between Neighbors, Loitering.” For The Gazette, Megan Woolard reports on a new 15-month pilot for an unarmed mediation responder team that “will serve as another response to 911 or other crisis line calls typically handled by local law enforcement… typically involving interpersonal conflict… such as noise complaints, disputes between neighbors, custody exchanges and loitering.” Dan Kornfield, who oversaw the creation of a similar team in Dayton, explained to the newspaper that there are a lot of calls for service that do not need an armed responder, a mobile crisis team, nor a fire department medic—that’s where a Mediation Responder Team comes in: “If you call 911 and it's not a fire and it's not a medical emergency, it's [often] automatically police, even if the issue is kids are loitering on the sidewalk, or my neighbor's trash can is touching my truck, a lot of things we wouldn't imagine our 911 calls are.” Kornfield added that Mediation Responder Teams can “provide both a better fit response to nonviolent disputes and also helps law enforcement by saving them time and energy from having to respond to noncriminal calls…. having a badge and a gun is counterproductive to a lot of those calls.”

In Dayton, where the first mediation responder model was launched in the country and has now become integrated into the city’s 911 response system, the mediation responder team handles thousands of calls for service a year “that police officers in the past used to handle,” Dayton Daily News reported. The team largely handles complaints like “unruly or misbehaving youth; barking dogs or other pet issues; disorderly individuals; tenant and landlord fights; and assistance with child visitation or custody exchanges.”

In Whatcom County, Washington, Mediation Team Responded To More Than 2,000 Calls For Service Just Last Year. Whatcom News reports on the county’s mediation team, called the Alternative Response Team, or ART—which the county describes as “a benefit [to] people having mental or behavioral health challenges, and benefit [to] our police personnel, allowing them to respond to other emergent calls requiring law enforcement intervention”—just last year responded to 2,410 calls for service, “acting as a vital alternative to law enforcement.” The team, dispatched via 911 to calls for service related to “welfare checks or disorderly conduct… fills the critical gap between jail and hospitalization.” The two-person teams average a 14-minute response time and focus on “de-escalation and connecting individuals to housing and mental health services” when needed.

3. Momentum For Community Violence Intervention Teams Across The Country.

In Birmingham, Alabama, “Homicides Drop 42% As City Highlights Community Violence Intervention Efforts.” For ABC News, Emily Cundiff reports on the CVI program, which operates in “one of the city’s neighborhoods most impacted by gun violence,” and, following the work of the CVI team, “according to city data, homicides dropped 42% year over year” in the neighborhood. The trained team of violence intervention specialists “focuses on street outreach, conflict mediation and connecting people at high risk of gun violence with resources such as mental health services, housing assistance and employment opportunities.”

In Berkeley, California, “Gun Violence Has Plummeted…[This CVI Team] Helped Make It Happen.” For Berkeleyside, Alex Gecan reports that the city “has seen the fewest shootings citywide in nearly a decade…[and] a network of violence intervention workers,” known as the Gun Violence Intervention and Prevention Program, “has been working to keep the numbers down.” The team’s street outreach workers coach people at risk of gun violence, “sometimes victims and their friends and families, sometimes those suspected of or likely to commit gun violence, sometimes both at once, at all hours of the day or night and often for hours at a time.” Since the program launched, the team has “had over 1,000 sessions and check-ins” with residents who are at risk of gun violence, “and they have made hundreds more overtures and interventions — mediating longstanding feuds before they can turn violent…”

In Milwaukee County, Mentorship Program Shows Early Promise In Youth Violence Reduction. The Milwaukee Courier reports on the latest data out of the county’s CVI team, called the “Credible Messenger Program,” which “intervenes in gun violence … and is staffed by individuals with lived experience and previous justice involvement who support youth through transformative mentoring.” As the Courier notes, the program “has made significant strides in improving public safety and supporting Milwaukee County youth involved in the justice system”—in just its first year in operation, the program “reported a 77% success rate for [reducing] recidivism and [increasing] pro-social behavior” for the youth entered into the program. The division also reported that “66% of the youth received at least 26 weeks of mentoring—essential for positive outcomes according to research, delivering more than 2,000 combined hours of mentoring.”