What To Read This Week

1. “Crisis Call Center In Texas Touted As National Role Model.”

Since the national 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline launched about a year ago, the hotline has seen record demand. But one 988 dispatch center in Austin, Texas is being heralded as a national model.

As Fred Cantu reports for Austin’s local CBS News affiliate, that “mental crisis calls used to require a dispatcher to send a police officer,” but now the Austin-based center routinely de-escalates mental health crises over the phone or dispatches civilian mental health responders, which results in “getting mental help to people faster while taking a load off other first responders.”

Monica Johnson, the national director of 988 and behavioral health at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, a branch of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, lauded the effort in Austin:

“People in Austin and Travis County have multiple access points to varying levels of mental health care, thus improving health outcomes and reducing unnecessary use of jail, ERs and inpatient hospitalization… This is a model worth shining a light on for the rest of the country to see.”

Dawn Handley, the center’s chief operations officer, explained to Austin’s local NPR station that one critical aspect of what makes the model successful is that Austin’s residents can also still call 911 if they are experiencing a mental health crisis. But instead of 911 operators defaulting to a police or EMS response, the caller is first asked whether they need help from “police, fire, EMS or mental health.”

If the caller needs mental health services, they are routed to Handley’s mental health team—who are integrated into the 911 response system and, if needed, can also be dispatched into the field. In other words, callers have multiple pathways to access help for a mental health crisis, each with an explicit option to request civilian-led mental health experts instead of a police response.

2. “It’s okay to need help. That’s the message that the city of New Orleans is spreading to the community.”

Earlier this month, New Orleans launched a civilian mobile crisis intervention unit, which, according to the city …

“is tasked to divert 9-1-1 non-violent mental health crisis calls away from police and other first responders to professionals trained in community behavioral crisis care response: 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and 365 days a year. The [unit] will exclusively serve Orleans Parish, and provide services for any person, regardless of age, who has notified the 9-1-1 system that they, or someone they are witnessing, is experiencing a non-violent mental health crisis.”

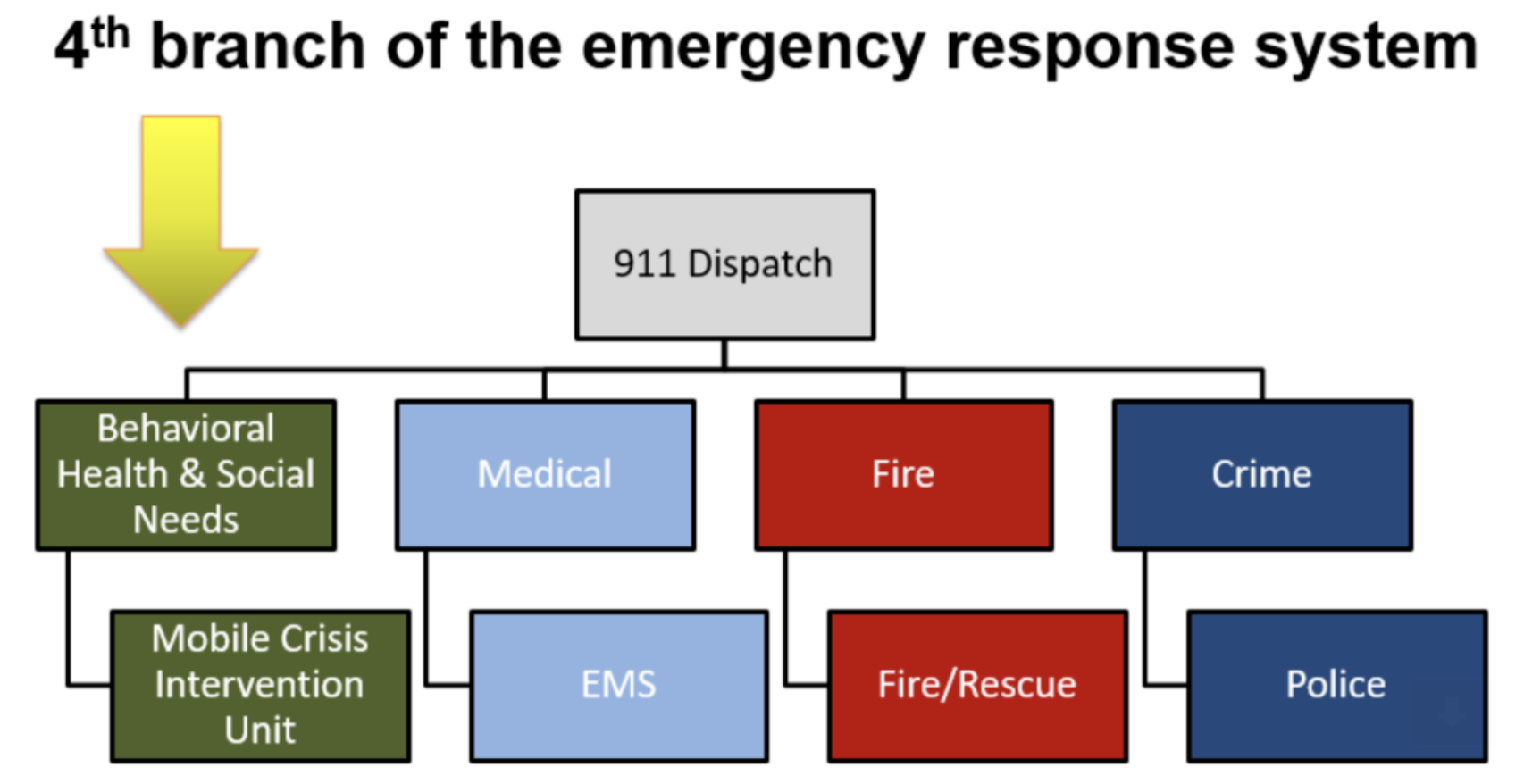

The city is billing the mobile crisis intervention unit as the mental health focused “fourth branch” of the city’s emergency services—sitting alongside police, fire, and EMS—which is a structural positioning that illustrates that city leaders intend for the unit to become a permanent and vital part of the city’s first responder infrastructure.

Graphic by RHD.

For WDSU, the local NBC television affiliate, Arielle Brumfeld reported that the mobile crisis intervention unit has “a staff of 15 trained mental health experts providing round the clock care” and “in just two weeks, the unit has helped nearly 100 people” and helped “free up law enforcement.”

Indeed, New Orleans Police Department Superintendent Michelle Woodfork told WDSU that the mobile crisis intervention unit allows the police department to “handle those calls that are higher priority and get to them quicker. It brings our response times down. So, this is an absolutely needed tool for the NOPD.” Indeed, calling the unit a “win-win for the community,” the NOPD reported “in its first week of operation”, the mobile crisis intervention unit resulted in a “36% burden reduction on NOPD platoon personnel.”

Writing for The Lens Nola, Nick Chrastil puts the importance of the mobile crisis unit in the broader context of the city’s long-time struggle to adequately address mental illness—and the accompanying shortcomings of heavy police involvement in mental health calls for service:

“The city receives thousands of such 911 calls every year – and in the past, police have primarily responded to them. But studies show that people with serious mental illness are more likely to be killed by police and that mental-health conditions can be exacerbated by squad-car lights, sirens and arrests. Too frequently, people in crisis end up arrested or involuntarily committed to a mental hospital. The hope is that, now, the endpoint of most crises will be stabilization and treatment, thanks to dedicated teams, trained in mental healthcare and de-escalation.

...At a time when police have struggled with hours-long response times, the effort should also free up officers to respond more quickly to violent crime calls, City Councilwoman Helena Moreno said. “We need to answer the community’s needs with the right resources and conserve NOPD officers to address urgent, violent crime,” Moreno said in a statement. “Crisis response by trained professionals has proven to be successful in other cities and even found to provide improved outcomes for people in mental health crises.”

3. “People want their loved ones to receive services in a crisis stabilization program rather than in an emergency room, jail, or in hospitals. The community wanted this yesterday.”

That’s a quote from Michelle Baker, executive vice president of Behavioral Health Services at Southcentral Foundation, who is part of a successful effort that will result in Alaska’s first crisis stabilization centers opening in Anchorage and Juneau this year.

Writing for the Juneau Empire, Clarise Larson detailed the new $18 million facility opening in Juneau that “will offer the first crisis stabilization center for adolescents and adults in Southeast Alaska [and] will have 23-hour access to mental health and substance use care and services at the center [,] along with short-term crisis residential stays of up to a week for patients who are unable to stabilize at the crisis stabilization center.”

Here’s a look at the new facility, courtesy of the Juneau Empire, which clearly presents as a calm and therapeutic setting in stark contrast to a jail or a hospital emergency room:

Wade Bryson, an assembly member for the city of Juneau, praised the new center telling Larson that it is “sorely needed.” That’s because, as Larson reported, “Alaska has long been among the national leaders in the rate in which people die by suicide and … currently leads the nation in the rate of young people who die by suicide.”

Meanwhile, in Anchorage, two centers will open this year that operate in roughly the same way as the Juneau center.