Three Things To Read This Week

1. Momentum For Mobile Crisis Response Teams Across The Country.

Los Angeles Study Finds The City’s Mobile Crisis Response Program Is “Address[ing] Critical Mental Health Emergencies” And Allows “LAPD More Time To Focus On Traditional Law Enforcement Efforts.” For The L.A. Times, Libor Jany reports on the city’s recently published new study on its mobile crisis response program which deploys “teams of licensed clinicians, social workers, community workers and therapists who work in pairs, responding to calls around the clock, seven days a week.” In its pilot year, “the program handled more than 6,700 calls… [and] already saved police nearly 7,000 hours of patrol time by freeing them up for other tasks.” The full report is worth your time, but here are three key takeaways:

Resolving Most Crises On-Scene: “68% of all calls are resolved on scene… spending the appropriate amount of time on-scene allows responders to fully assess the situation and apply the necessary level of intervention, ensuring individuals receive the right care and support. This approach reduces the likelihood of escalation, repeat calls, or redirects to LAPD.”

Significant Time Savings For Police Officers: The mobile crisis response team “saves LAPD officers’ time, during which officers are able to respond to higher risk calls for service… 6,900+ hours of patrol time saved… Beyond providing more appropriate care to individuals affected by crises, [mobile crisis responders] also allow LAPD more time to focus on traditional law enforcement efforts.”

Strong Perception Of Effectiveness Among 911 Dispatchers: “83% of respondents believe the unarmed crisis response programs are effective... most respondents viewed the programs positively…”

Indiana “Funds Mobile Response Units… To Help Respond To Mental Health Crises.” For WFYI, Benjamin Thorp reports on state leadership in Indiana investing $5 million “towards the expansion of mobile crisis response units in five counties… [where] teams of responders will help residents in the midst of mental health or substance abuse crises… and reduce calls to police or visits to the emergency room.” State officials explained to the news station that the five counties were selected “based on data showing high rates of behavioral health crises and limited [existing] mobile response infrastructure.”

Arkansas Investing $10 Million Into “Statewide Mental Health Crisis Hub.” The Stuttgart Daily Leader reports on the state’s Department of Human Services investment into mental health crisis response across the entire state and led by the University of Arkansas. The statewide effort “includes a 24/7 centralized call center, mobile crisis teams” as well as integration with other vital services around the state including other first responders, hospitals and social services. [Seven regional sites will be] fully operational by mid-2026,” Insight Into Academia reported.

2. Cities Expanding Access To Mental Health Services Through Integration With 911.

In Washington State, “Trained Mental Health Counselors [From 988, Are Increasingly] Embedded Inside [911] Call Centers.” For The Washington State Standard, Conor Wilson reports on the state’s “ambitious effort to overhaul [a] behavioral health response system… [that sees] large numbers of calls are now diverted [to mental health experts and] away from emergency responders like law enforcement.” Inside the call centers, to determine which responder is the right responder for the caller, “one of the biggest innovations has been conference calls, where a 911 call receiver and 988 counselor are on the line at the same time with a caller—able to give them advice as they wait for first responders.” Bringing the 911 and 988 experts together “opens up many opportunities to support callers and maintain a ‘no wrong door approach… no matter who you call and where you go, we’re going to get you to the right people.’”

In Calvert County, Maryland, County Leaders “Integrated 988, 911, And The Mobile Crisis Team.” For The Baynet, Carrie Cabral reports on the “landmark collaboration effort… to get people experiencing mental health crises the help they need, when they need it… [and] reduce the burden on 911.” The integration allows the two expert teams at 911 and 988 “to work together …to ensure cohesiveness between first responders and to make sure people get the best possible outcome no matter the reason for their call.” County leaders laid out a directive so that “each component plays a unique role,” including 988 which “provides immediate emotional support and triages crises with trained mental health counselors,” then 911 which “addresses emergencies requiring law enforcement, fire or medical services” and then the mobile crisis response team which “delivers on-site, specialized care” for mental health-related calls for service.

Los Angeles County Expands Mental Health Access Through 911. County leaders have expanded an ongoing collaboration between 911 and 988 in the county, “that helps ensure individuals in mental health crises are connected to the most appropriate care,” Random Lengths News reported. The program “enhances emergency response by directing mental health-related 911 calls to trained 988 crisis counselors for immediate support… so that law enforcement can concentrate on protecting communities while individuals experiencing mental health emergencies receive the specialized care they need.” The expansion “builds on the success” of existing collaboration between 911 dispatchers and 988 crisis counselors in cities across the county.

3. Community Violence Intervention Programs Helping To Reduce Violence.

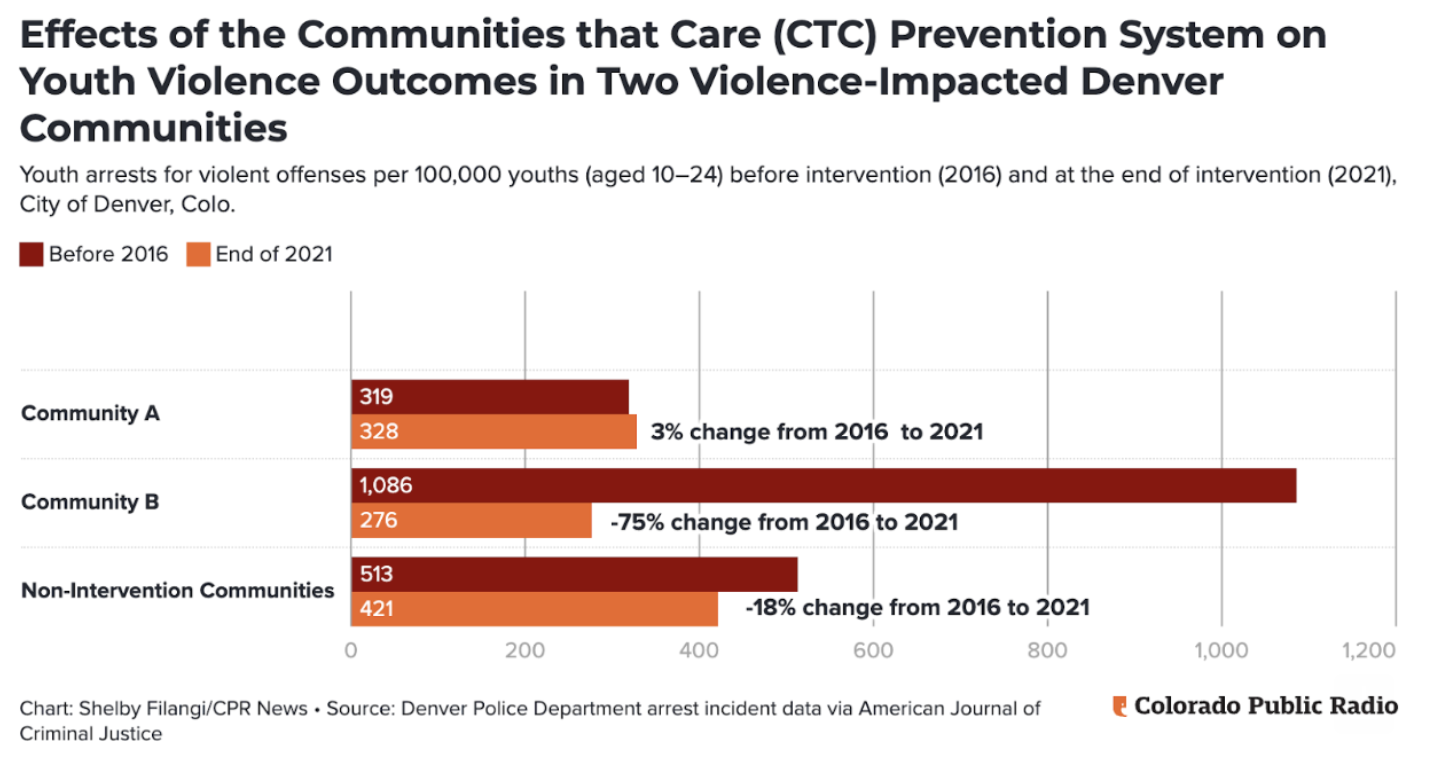

In One Denver Neighborhood, CVI Program Helped Fuel A “75 Percent Decrease In Youth Arrests For Violence.” For Colorado Public Radio, Kiara DeMare and Arlo Pérez Esquivel report on a CVI program in the Park Hill neighborhood of Denver, where “a decade ago, youth arrests for violent offenses were high compared to the national average,” but saw “a 75 percent decrease in youth arrests for violence” from 2016 to 2021, when the CVI program was operational in the neighborhood. The CVI program was multi-faceted, the news station notes, it focused on both a concerted effort to “connect teens to their neighborhood… [forging a feeling of being] bonded to your community [which] can be a protective factor” and a partnership with “doctors and other medical staff serving the neighborhood to start using a standardized screening tool to identify the youth most at risk of violence.”

In Detroit, A “50% Drop In Violent Crime In Some CVI Zones.” For Fox News, Hilary Golston and Jack Nissen report on the city’s CVI teams “press[ing] down on the city's crime rates, showing the strategy of targeting potential sources of violence before they break out is working.” Between May and July of this year, the city’s seven CVI zones (each zone “covers approximately 3.5 to 4.5 square miles”) reported back “a 30% drop in homicides and non-fatal shootings” and “two areas on Detroit's west side” saw “a 50% reduction across the same metrics.” As Fox notes, “while police are key to stopping crime, this program prevents it from happening in the first place… ‘law enforcement responds after the fact. What these groups are doing is getting in there before anything happens…’”

In Chicago, CVI “Program Participants Earn High School Diplomas.” For CBS News, Jason Cooper reports on a group of young people “working to turn their lives around” through participating in Chicago CVI program, known as CRED, earned their high school diplomas, last week. The community violence intervention program that includes comprehensive wrap-around services, also helps its participants to complete their education. The news station noted that CRED staff members “helped the new grads earn their [high school] diplomas” with “family members, life coaches, and outreach workers all there to cheer on the graduates.” Since the CRED program was first founded 2016, it has helped 400 participants [to earn] high school diplomas.”

A recent study from a team of researchers from Northwestern University examined the outcomes of 324 men who participated in the Chicago CRED program, between 2016 and 2021, and found that the men who completed the full 24-month CRED program were “more than 73% less likely to have an arrest for a violent crime in the two years following enrollment compared to individuals who did not participate.”