Three Things To Read This Week

1. Three More Cities Launch Mobile Crisis Response Teams:

In Seattle, Washington, “the city’s 911 dispatchers are now directing a team of mental health professionals,” known as the Community Engagement and Response (or, CARE) team, to help “people on the street who need supplies, referrals to resources, transport or just someone to listen,” as Liz Radel reports for KUOR, Seattle’s NPR station. Here are two examples that already demonstrate the value of the CARE team’s work:

“Temperatures were dropping and most shelters were already full” when the CARE team encountered “an individual who was looking to get into shelter.” Chris Inaba, a member of the CARE team, told NRP that he and his partner “contacted our resources, and we were able to find the person a bed, and then we provided the transport as well.”

As Nimra Ahmad reports for Seattle’s local PBS station, the CARE team also helped a 70 year-old woman find shelter after she was evicted from an apartment building where she had lived with her husband for twenty years until he died the year before. The CARE team was “able to reserve a bed for her at the Downtown Emergency Service Center’s Crisis Solutions Center, but now came the hard part: convincing her to go.” Ahmad describes what happened next:

“For nearly three hours, [the CARE team] gave this woman their full attention. They attempted to connect her with a nearby storage unit where she could safely store her belongings now strewn across the alley, but, still in shock and completely focused on returning to her apartment, she refused the offer. They spoke with the building’s property manager to advocate for her, but to no avail. After a lot of negotiating and waiting patiently as the woman rummaged through her belongings to determine what she’d have to part ways with, they got her in the car, drove her to the Crisis Solutions Center and let a case manager take over. In the end, despite her initial resistance, she thanked the CARE Team.”

Right now, as Radel reported for NPR, the CARE team “is small, there’s a single team available from 11 a.m. to 11 p.m. each day and their response area is confined to the downtown core.” However, the plan is for CARE to expand throughout the city after it gains footing downtown.

Notably, one likely unnecessary friction to scaling the CARE program could be the city’s dual dispatch model in which 911 sends both the police department and the CARE team to calls. This dispatch model differs from most of the mobile crisis response programs highlighted in Safer Cities in that most programs dispatch only the mobile crisis response team and then allow those responders to request police back-up as needed. The downside of the dual response model is both that it expends police resources on calls that do not require a police response and that the presence of sirens and an armed officer can interfere with the successful resolution of a call for service.

Santa Monica, California, also launched its mobile crisis response program, known as Therapeutic Transportation, which is a “specially trained team that will eventually be on call 24 hours a day to assist anyone in Santa Monica suffering from mental health-related trauma.” As Scott Snowden reports for the Santa Monica Daily Press, the “team will have the ability to do a psychiatric transport to an urgent mental healthcare facility or hospital, as well as impose a 72-hour psychiatric hospitalization for a person who is deemed to be a danger to themselves or others.” Two quotes from the Daily Press story that capture the aim of the city’s mobile crisis program:

They “help people in our streets, [and] help reassure our residents that there is help on the way for those people that they are wary of and it will help people regain their lives … because what’s happening right now is in many cases, homeless individuals on our streets get emergency care or no care. And they have no real chance to regain their lives and become productive residents.” Santa Monica mayor Phil Brock.

“Our hope is that we can intervene, when and where we can, rather than law enforcement or the fire department, so it frees up the resources for the city to divert to more severe emergencies.” L.A. County Department of Mental Health Director Lisa Wong.

In Wayne County, Michigan, which encompasses the city of Detroit, “the Detroit Wayne Integrated Health Network is hitting the road with mobile crisis units this week in an effort to help local children and adults in crisis.” As Detroit’s local ABC affiliate explains, the program will launch with four teams and be “available Monday through Friday from 7 a.m. to 3 p.m. for adults only. Eventually, though, the group hopes to provide around-the-clock services for children and adults.” Right now, the program is not integrated into the 911 call center, but leaders hope that soon mobile crisis response will “be able to connect with 911 so they can be dispatched if people call with a crisis that doesn't require a police response.”

In an interview with Kara Berg from Detroit News, the Vice President of Integrated Health Network, the organization that manages the mobile crisis program, highlighted three features of the program that county residents should know:“Each team has a clinical social worker and a peer recovery coach with lived experience [and] the teams can go to someone's home or meet them wherever they are as long as it’s in Wayne County.”

“They can connect people to community resources they may need, such as shelters or food banks, or to outpatient mental health or substance abuse resources.”

“They can also transport people to crisis stabilization units or hospitals if they need more care than the mobile units can provide.”

2. Three Additional Programs Expanded To Provide 24/7 Service:

Indianapolis, Indiana’s “clinician-led community response team now operates 24/7,” Rachael Wilkerson reports for WRTV, the city’s local ABC affiliate. The team, which addresses issues related to homelessness, mental illness, and substance use, is dispatched through the 911 system. The operations director for the community response team told the news station that the public can have confidence in the fact that “when they call 911 and request the clinician-led response team there are professionals who will arrive to care for whoever is in need. We're educated and we know what we're doing. We know how to handle these calls.”

Placer County, California, which is part of the Greater Sacramento metropolitan area, has a mobile crisis team that now operates 24 hours a day, 7 days a week … to address mental health crises by utilizing their mental health clinicians, psychiatric nurses and peer advocates to develop safe supportive coping plans.” For Sacarmento’s local Fox News affiliate, Matthew Nobert reports that the mobile crisis team responded to over 500 calls last year, “meet[ing] with those in need in any setting like parks, schools, shelters, homes or parking lots.” The program also has expanded from serving “mainly adults to now serving youth and families.”

On the University of California, Davis campus, the mobile crisis team now promises “in-person support, offered 24-7 on campus,” according to reporting from Ashley Mowreader for Inside Higher Ed. The program is housed within the university’s fire department, and is composed of “health education specialists” who are “licensed paramedics and [have] completed a program in lay counseling.” The “team drives around in a special red van stocked with food, bottled water and toiletries. The van has benches in the back so staff can provide care in private, and it can also accommodate a person who uses a wheelchair.”

“On average, the mobile help line receives between five to six calls per day … Most commonly, students call to get help with anxiety, navigating interpersonal relationships, medical resource navigation, thoughts of self-harm, academic pressures and concerns or housing support.” The fire department chief told Inside Higher Ed that the team isn’t simply a crisis response unit, but also “a crisis-prevention team that aims to normalize asking for help early, before a crisis—and when one can’t be averted, working to support after.”

3. Three Ideas To Make Mobile Crisis Response Teams (Even More) Effective:

Provide Formal Training In Suicide Prevention. In the prestigious Journal of American Medicine, pediatric emergency room physician Dr. Rachel Cafferty and colleagues advise that mobile crisis response teams—and all “frontline emergency clinicians and staff”— should receive “formal training in suicide prevention, including standardized screening practices to improve risk recognition, assessment and targeted interventions.” For context, the authors explain that “pediatric emergency medicine clinicians have witnessed the worsening public health epidemic of mental illness in children and adolescents” and “suicide remains the second-leading cause of death for children and adolescents in the US.” At the same time, “80% of children and adolescents who die by suicide interfaced with the health care system in the year prior to their death, indicating an opportunity for improved risk recognition and intervention.” Hence, the need for formal suicide prevention training.

Transport Unhoused People To Shelters During Inclement Weather. As temperatures dip below freezing this week in Albuquerque, New Mexico, the city’s third branch of public safety, the Albuquerque Community Safety Department “has created an overnight, emergency transportation hotline for people who need to get out of the cold and to shelters” and “will be offering an overnight transportation van for anyone that needs a ride to a shelter.” Of course, transportation is a hollow promise of safety from the elements if there are no shelter beds available, which is why the city has “expanded its shelter capacity and is ready to provide a warm bed to anyone that needs it.”

Flashing Green Lights. In New York, a “new law allows [mobile] crisis team members to install flashing green lights in their vehicles to alert other drivers they are on the way to a mental or behavioral health emergency.” The mobile crisis teams “are allowed, if necessary, to exceed the speed limit, but not at a dangerous speed. [Moreover,] unlike red lights on police and fire trucks, drivers are not required to yield to flashing green lights, but are strongly encouraged to do so.” Pete Harckman, a New York State Senator, told CBS News New York’s Tony Aiello, that the lights are necessary because “when you have behavioral health crisis responders going out [on a call for service], they are no different than an EMS technician, because in a health crisis seconds matter.”

What A Difference A Year Makes:

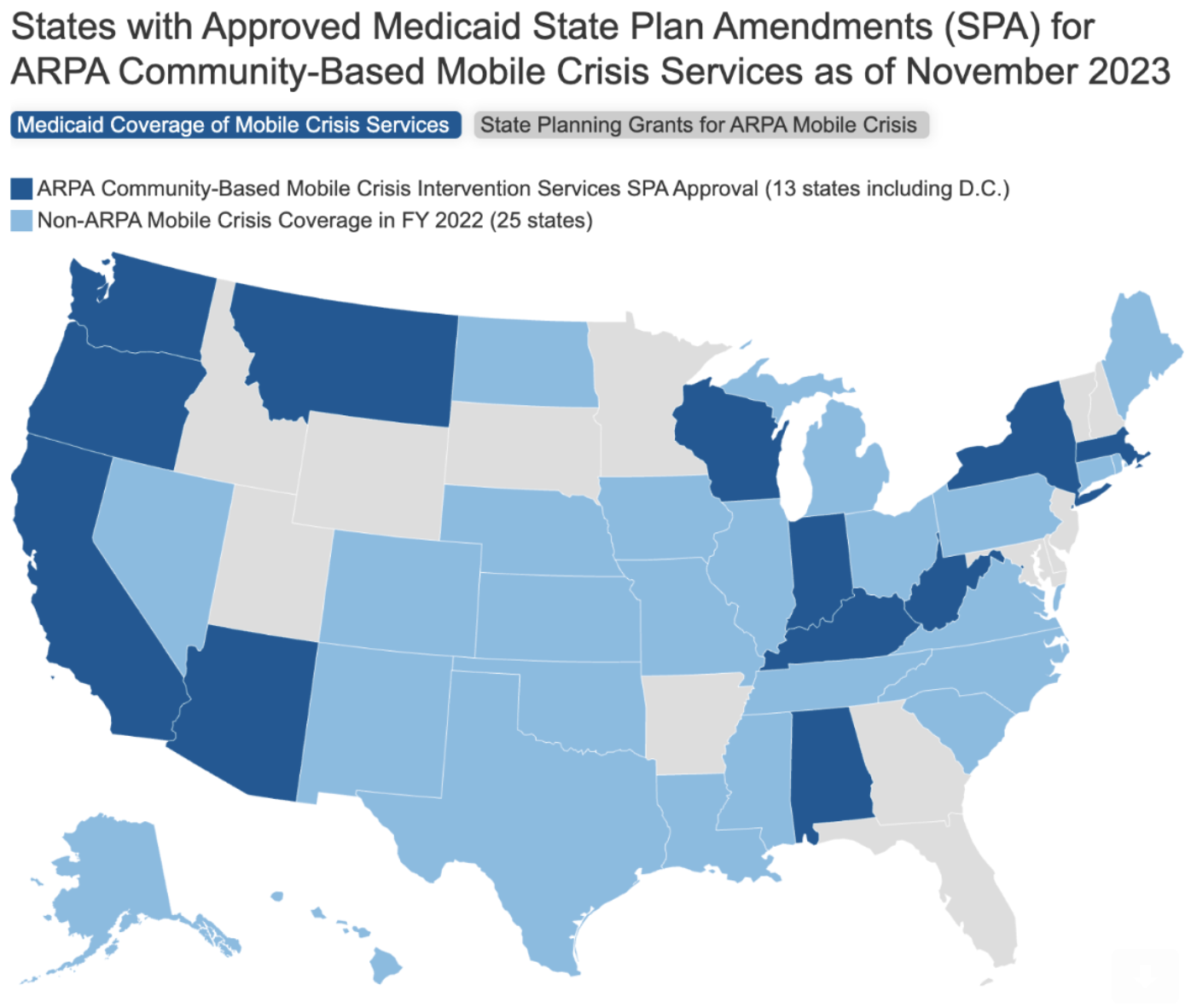

Safer Cities reported in late 2022 that Oregon had become the first state in the country to receive federal approval to obtain Medicaid reimbursement for mobile crisis response services. Today, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, a dozen additional states are approved to seek reimbursement. The following KFF graphic illustrates the progress: