Three Things To Read This Week

1. Hospital-Based Violence Intervention Programs “Help Survivors Of Gun Violence Heal—Both Mentally And Physically.”

In Hennepin County, Minnesota, Next Step Is “Reducing Re-Injury And Re-Hospitalization” From Gun Violence. For WCCO, Susie Jones reports on Next Step, a hospital-based violence intervention program that combines efforts from healthcare professionals, who provide medical and trauma services while the person is hospitalized, as well as mental and behavioral healthcare professionals, who help victims obtain ongoing trauma counseling. The effort has helped nearly 1,000 survivors of gun violence “reduce re-injury and re-hospitalization… helping survivors heal—both mentally and physically”

Kentral Galloway, the director of the program, explained to the news station that “survivors [of gun violence] often face challenges… people are traumatized, so helping them deal with their trauma… [everything from] victims having a hard time sleeping or eating…. [to] not wanting to leave their house [or] go to certain areas of the city… [to working with their] families to make sure they have cooler heads, and don't go back out in the community and do something irrational” is part of the work of the experts in the program.

WCCO detailed the story of Sophia Forchas, a 12-year-old who “was shot in the head” during the August mass shooting at Annunciation Catholic Church and School in Minneapolis, who is a patient in the program and whose recovery “many didn’t think was possible.” But the program’s experts helped Sophia to do just that, and “last week, she went home from the hospital… now that recovery goes from being able to survive, to being able to fully function physically, to the mental healing from such a traumatic experience.”In Milwaukee, Project Ujima “Helps Wisconsin Families Heal.” For Spectrum News 1, Haley Kosik reports on the city’s hospital-based violence intervention program that is embedded into the “emergency department of Children's Wisconsin” and “connects children and their families to resources that help them overcome the traumatic effects of violent events… breaking the cycle of youth violence and trauma.” The team at the hospital, composed of physicians, “social workers, public health nurses, mental health support staff, and volunteer peer counselors” are deployed when a young patient is admitted to the hospital because of violence. The team treats the physical wounds and then connects them with “services like therapy, medical follow-up, home-based counseling, and support for grief and trauma… [as well as connections to] affordable housing, food and employment.”

Lamicka Lovelace, who oversees the program, explained to the news station that as soon as a patient who has been a victim of violence comes into the ER, the intervention staff are paged and go into action immediately: “They will meet the family right there in the emergency room to talk about services and resources. It’s letting them know that, yes, you did go through this traumatic incident, but hoping that through our resources and interventions, you can get through this.”In Cincinnati, Ohio, New Hope And Shield Violence-Intervention Program Reports “Early Results” To City Health And Safety Leaders. Citizen Portal reports on the Hope & Shield Network—a hospital-based violence intervention program that University of Cincinnati Medical Center and Children’s Hospital network launched about a year ago—and its “early results” that physicians presented to the city council at a Public Safety and Governance Committee hearing. The physicians explained to city leaders that in the first six months of the hospital-based violence intervention program, they enrolled 50 patients who received specialized care and “none of the 50 enrolled patients had a documented repeat injury in the six-month window to date.”

The hospital network program “provides in-hospital bedside engagement and post-discharge wraparound services—case management, job readiness, housing navigation and food assistance—targeting victims of intentional violence” throughout the city. The physicians in the program carry specialized “trauma pagers so they can be notified when an injured patient arrives and can immediately engage with patients and families during inpatient stays and at outpatient follow-up.”

Related: For WYPR in Baltimore, Wambui Kamau reports on a first-in-the-nation effort at Sinai Hospital that is “testing a new way to stop violence before it reaches the emergency room: the Digital Violence Responder.” The digital responder, a staff member at the hospital who is trained in de-escalation, “monitors social media for credible threats and alerts a call center that sends trained mediators to defuse the conflicts.” The digital responder model, violence experts explained to the news station, “builds on community-based violence interrupter efforts, where nonprofits use trusted messengers — and now digital tools — to intervene early.”

2. Momentum For Overdose Response Teams Around The Country.

In Tennessee, “Hamilton County’s Overdose Response Team Hits The Streets To Save Lives.” For News9, Katie Glanton reports on the county’s new “Overdose Prevention Team,” a first-of-its-kind in the state, which is deployed to overdose-related calls for service to help people “struggling with opioid addiction get immediate, on-the-ground treatment and recovery support.” The team, composed of “a paramedic and a certified peer support specialist,” respond to calls across the county in “Quick Response Vehicles, they deploy directly into neighborhoods” with “medication and assisted treatment to any willing participant at no cost, with personalized connections to local resources for recovery” after the initial overdose crisis has been resolved.

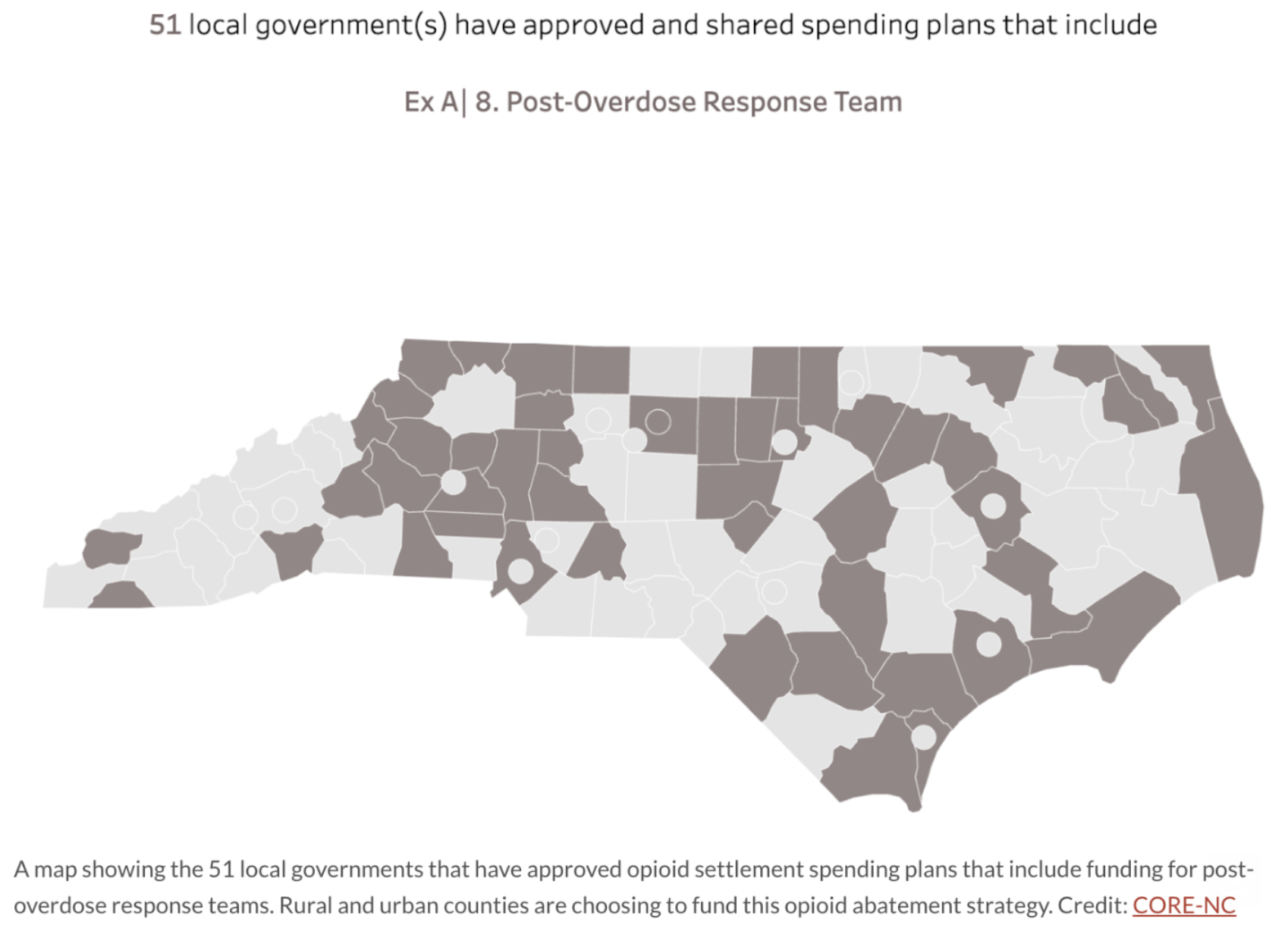

In North Carolina, “Counties Across [The State] Are Deploying Post-Overdose Response Teams.” For North Carolina Health News, Rachel Crumpler reports on a new effort gaining steam in more than 50 counties across the state—when an overdose call comes in, 911 dispatchers are deploying post-overdose response teams, who “provide dedicated follow-up support to people with substance use challenges — sometimes in their homes, sometimes at the doctor’s office or even at a gas station” and provides them with the resources they need, connection to “detox programs, recovery meetings, medications for opioid use disorder and more — all tailored to each person’s needs.”

In one county, Carteret, which has had a post-overdose response team in operation for nearly three years, the results are clear: “Since the team began operating, overdose metrics in the county have improved a lot… a 77 percent decrease in overdose deaths and about a 90 percent decrease in overdose 911 calls from 2022 to 2024… [and] more than half of the individuals the team has worked with have entered some form of treatment.” It’s “a major shift from the county’s previous approach” to overdoses which saw police, EMS, or other first responders deployed and transport the patient to a hospital. But “many people who survive overdose… who go to the emergency room may not get their withdrawal symptoms treated or receive medications for opioid use disorder. Without further support, repeat overdoses — and even deaths — are common.”

In The Bronx, “Mobile Overdose Response Van Launches.” For The Riverdale Press, Olivia Young reports on the borough’s new Mobile Overdose Response van—“a resource designed to target areas of high drug use, or hotspots”—on patrol with trained staff who connect people experiencing an overdose with Narcan and connection to “rehabilitation and other services in place of jail time.” The van provides “a private space where staff can ask a client intimate questions… while offering clothes, food and other necessities” to patients who need additional care and services. With the van on patrol, or stationed outside various NYPD precincts, the van has allowed for “response [that] can now be immediate.”

Arlene Machado, a case manager with the overdose response program, explained to the newspaper that “Instead of having the NYPD wait for us to get there [following an overdose call for service], we’re right outside… [and] get this person service right now. This person needs to go to the emergency room … or this person is in active withdrawal — we can help.”

3. Study: Mobile Crisis Response Teams Deliver Real Results And Savings For Cities.

A new working paper, published by researchers at the National Bureau of Economic Research, evaluates Durham, North Carolina’s HEART program, which diverts nonviolent 911 calls from police to mobile crisis response teams. The researchers found that “HEART reduces crime reports, arrests, and response times—primarily through civilian phone and in-person responses, rather than police-civilian co-responses,” and that it “is a fiscally self-sustainable intervention” that fosters public trust. The full paper is worth your time, but here are some key findings:

Fewer Arrests, Faster Response: “Crime reports declined … over 50 percent relative to baseline, and arrests dropped … from a 5 percent baseline.” The study also found that “response times decreased for both program and police responses, but the decline is nearly twice as large for HEART responses.”

Greater Trust And Engagement: Rather than discouraging 911 use, “HEART does not deter future calls… [residents] served by HEART generate slightly more follow-up calls than those served by police, yet this increased engagement does not translate into higher rates of violence.” This suggests “civilian teams handle emergencies without escalation and may encourage continued, constructive use of emergency services.”

Self-Sustaining: “The average HEART response costs $1,191 but generates estimated fiscal savings of $2,093 per call… The resulting net savings of $902 per call… means that the program pays for itself through fiscal externalities.” They add that “95 percent of respondents report a positive willingness to pay for the program, with the mean valuation being $102.91 per year—more than eight times the program’s per-resident cost.”

Frees Police To Focus On Serious Crimes: The authors found that “HEART reduces crime reports, arrests, and response times” and that these effects “are driven by the program itself rather than changes in enforcement behavior,” suggesting civilian teams are “diverting low-risk calls from the criminal legal system” so police can concentrate on higher-priority incidents.