Three Things To Read This Week

1. Momentum Grows For Integrating Mental Health Crisis Experts In Dispatch Centers

In Missouri’s Springfield-Green County, Mental Health “Crisis Specialist To Now Work Inside 911 Full-Time.” For The Springfield News-Leader, Marta Mieze reports on county leaders bringing more mental health expertise into the Springfield-Green County’s 911 emergency dispatch center “to more effectively address mental health crisis 911 calls” in the region by “decreas[ing] the number of responses from police to individuals who are experiencing mental health crises” and dividing those calls to trained mental health experts instead.

April Ford, who oversees the county’s 911 dispatch center, explained that the integration “helps each team to communicate better, learn how each person is trained, how calls to each agency can differ and to better understand the crisis specialists’ skills in action…. not all callers want a law enforcement response and [some] may [instead] need resources or to speak with a 988 crisis specialist to assist with mental health needs.” Ford, who also sits on the statewide 911 Service Board Training Committee, said that experts from around the county and state “collaborated on training and setting up procedures to make the integration work… [so that] the 988 crisis specialist can help not only with calls on site, they are also able to engage with the 911 team about available resources that they previously were not aware of [and the county’s] crisis team will relocate additional [mental health] team members to the 911 center as needs arise.”In Colorado, Colorado Springs Now “Allowing Dispatchers To Connect Callers Directly With The Mental Health Hotline.” For The Colorado Springs Gazette, Grace Brajkovich reports on a new partnership with 988 in the county which “provides the Colorado Springs community with more mental health resources in moments of crisis.” A spokesperson for the Colorado Springs Police Department, who oversees the 911 dispatch center, explained to the newspaper that “a lot of (mental health related) callers just need someone to talk to. We often send an officer out to provide them with the resources they need…. [but] sometimes when you are experiencing a mental health crisis, you don't always want to talk to the police. That isn't always the most appropriate option.” The new agreement will allow “non-emergency callers [to] be referred to 988… [and if needed] the Community Response Team will provide emergency mental health care for those in need of immediate attention.”

In Florida, New Law Includes “988 Helpline In The State’s Panoply Of Mental Health Services.” For Florida Politics, A.G. Gancarski reports on Governor Ron DeSantis signing into law House Bill 1091 which provides the mental health hotline with “statewide interoperability with the 911 system and to provide individuals with rapid and direct access to the appropriate care.” The bill officially adds the mental health hotline as part of the state’s public safety infrastructure which includes “mobile response teams, crisis stabilization units, addiction receiving facilities, and detoxification facilities” and will help ensure standardization around “service delivery, quality control standards, training and certification for staff members” statewide.

Related: Los Angeles County launched a new centralized dispatch center that targets people experiencing homelessness to “to quickly connect [them] with housing,” Kahani Malhotra reports for LAist. The Emergency Centralized Response Center, or ECRC, “centralizes intake to the various services and programs for unhoused individuals run by a host of county and city departments, agencies and outreach teams.” Before the centralized dispatch was created, the county “would have all of these outreach teams descending upon this one site, which is not a good use of resources… [but now as a] centralized information hub, officials say the dispatch center can coordinate across several agencies and teams to receive requests for services and direct a group of 150 outreach teams to help provide timely interim housing and necessary support.”

2. New Safer Cities Polling On Community Safety Departments

To help modernize the public safety infrastructure in a city or county, local leaders are launching Community Safety Departments—what local leaders call “the third branch of public safety,” co-equal with the police department and fire department, and which house a city’s unarmed crisis responder teams.

Three years ago, Albuquerque—under Mayor Tim Keller’s leadership—launched the country’s first community safety department. Last year, the department opened its own headquarters. And just last month, the city’s Community Safety Department announced it had reached a historic milestone—having “responded to over 100,000 calls.” Now, Albuquerque’s Community Safety Department has become a national model for other cities and counties launching these departments.

To gauge public support for Community Safety Departments as part of a city’s public safety infrastructure, Safer Cities recently conducted a national survey of 2,503 registered voters.

First, we explained that “some cities have created community safety departments that, like police departments, are umbrella agencies that divide first responders into divisions based on their responsibilities and their expertise.” We explained that “in the same way that police departments are organized into units such as the traffic unit or robbery-homicide unit, community safety departments also have separate units.” We then defined what some of those units are:

Some “include mobile crisis response units that dispatch behavioral health experts to 911 calls involving mental health and substance use related issues.”

Some “might handle matters such as picking up dirty and discarded needles from parks and sidewalks…”

Others “might address minor traffic violations and parking disputes.”

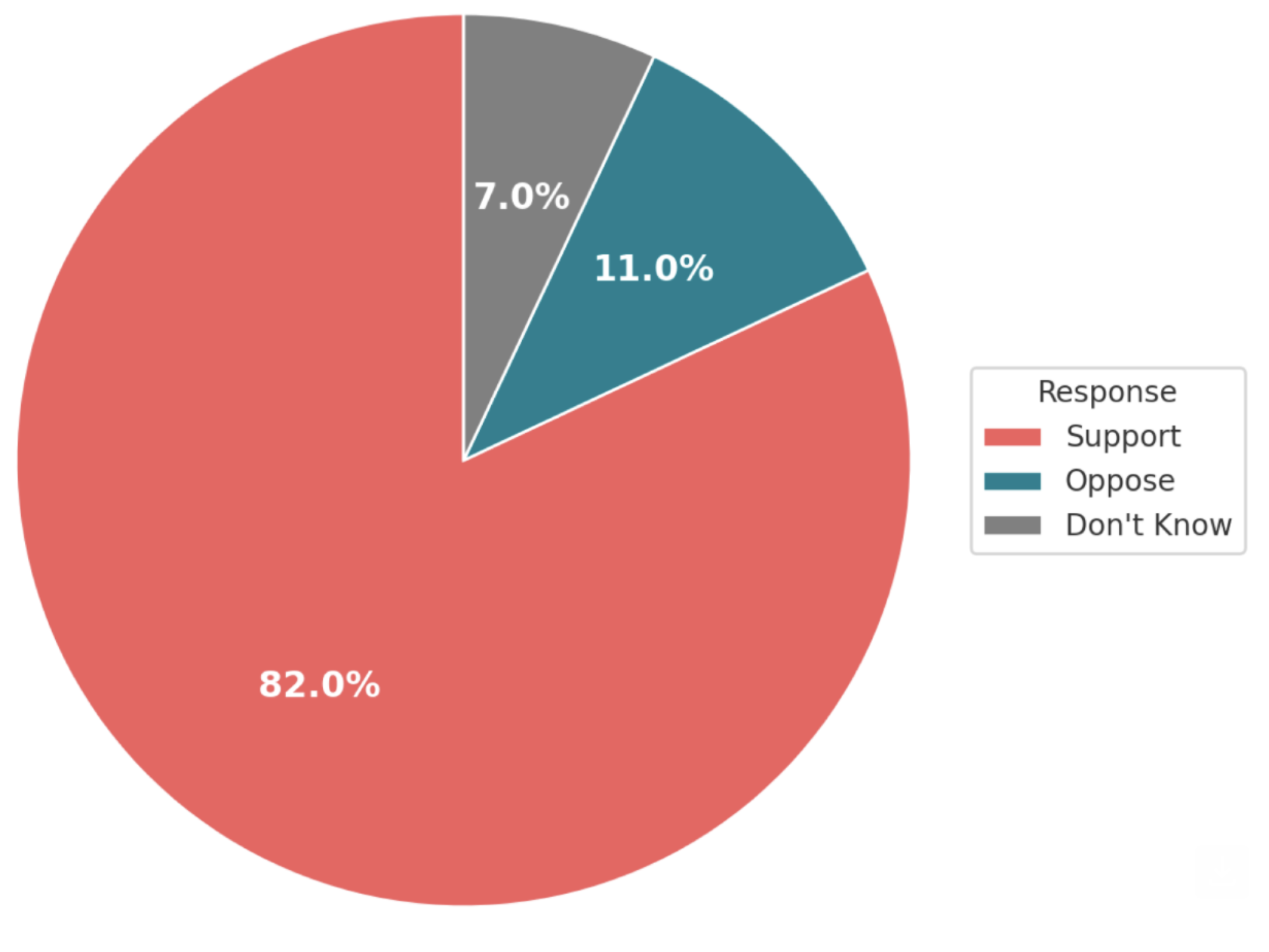

We then asked if their city was “creating a community safety department that would function as a separate and coequal city department alongside the police and fire departments,” would they “support or oppose” that effort? Here are the results:

82% Of Americans Say They Support Their City Creating A Community Safety Department That Functions As A “Separate And Coequal Department Alongside Police And Fire Departments.”

These results also reflect broad bipartisan support, including 90% of Democrats and 78% of Republicans who support their cities creating a community safety department.

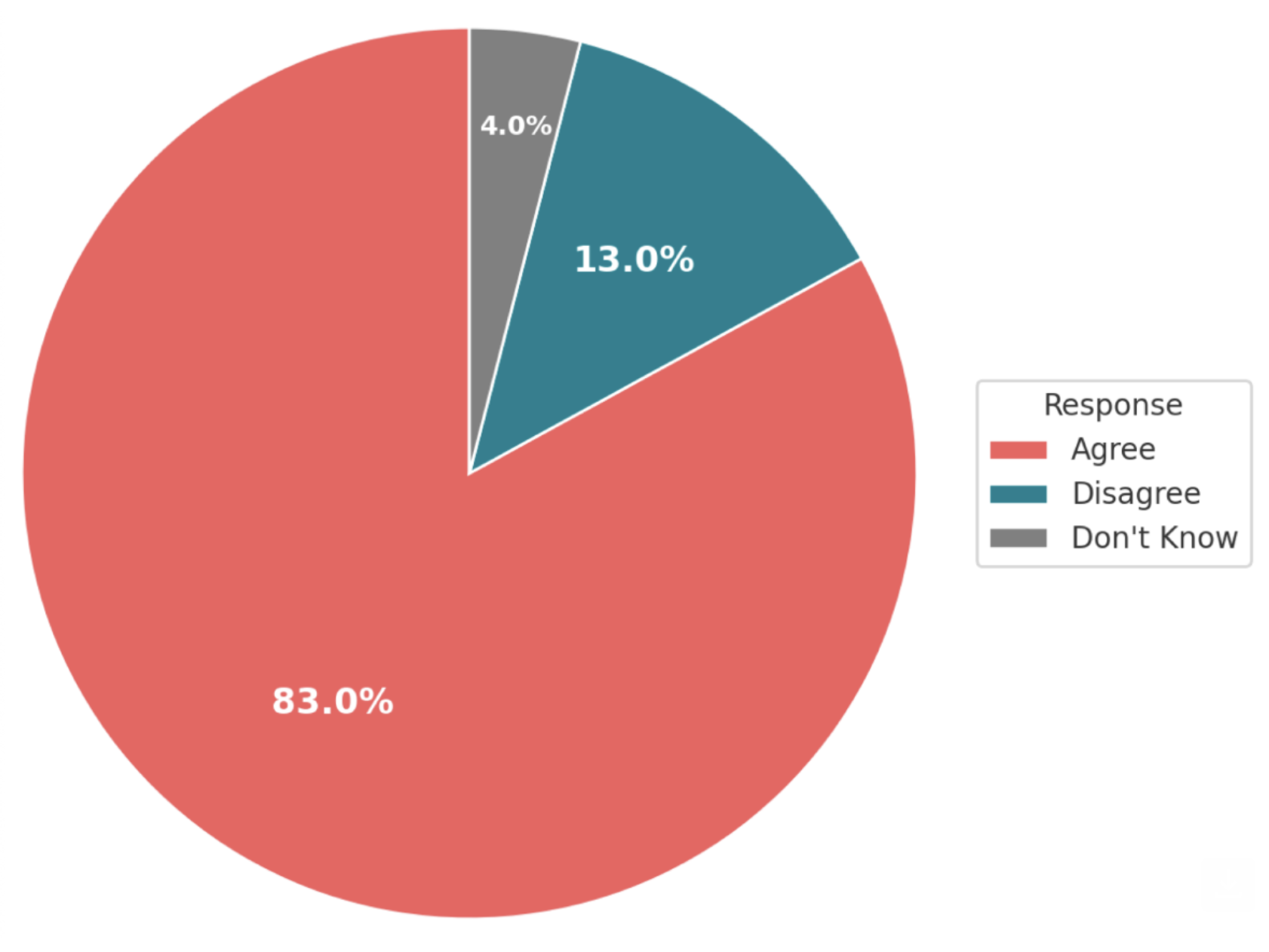

We then asked respondents if they “agree or disagree” that “community safety departments allow police departments to focus on solving serious crimes.” Here’s what we found:

83% Of Americans Say That Community Safety Departments “Allow Police Departments To Focus On Solving Serious Crimes.”

3. Across The Country, States And Cities Double-Down On Narcan Access

Colorado Announces $3 Million Grant To Boost [Narcan] Supply As Data Shows Drop In Overdose Deaths. For The Denver Post, Nick Coltrain reports that Colorado leaders will use $3 million from the state’s opioid settlement fund “to provide the overdose-reversal drug [Narcan]” to more locations around the state. Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser made the announcement as the state saw “a 15.6% drop from 2023’s [overdose] total… [with] officials crediting the availability of [Narcan]... for helping to blunt the health crisis.”

In Oklahoma, State Revives Narcan Vending Machine Program. For KFOR News, Abigail Franklin reports that the Oklahoma Department of Public Health “is redistributing the life-saving Narcan vending machines” across the state “to help curb overdose deaths,” following a pause in the program last year. Mark Woodward, with the Oklahoma Bureau of Narcotics, explained to the news station how important this renewed effort is in the state: “We hear stories all the time from parents who used it when they found their teenager who was overdosing… or their adult loved ones who’s in their seventies or eighties with dementia, overdosing because they forgot whether they took pain medicine… and a loved one was able to administer it.”

In Louisiana, Pointe Coupee Parish Installed County-First Narcan Vending Machines At Local Libraries. WAFB News reports on the first Narcan vending machines being installed at four public libraries around the parish in an effort “to reduce opioid overdoses… by equipping residents with the tools they need to save lives.” The vending machines offer “free 24/7 access to Narcan, Fentanyl testing kits, and educational materials on substance use and overdose prevention.”

In Georgia, Newton County Sheriff’s Department Installed First Narcan Vending Machine At The County Jail. For The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Chaya Tong reports on the first Narcan vending machine “in a law enforcement facility” installed in the state. The move comes just months after the Georgia legislature made the units legal across the state. First responders around the state are “trained in the use of the medication, and many carry doses with them on calls… [and] equip vehicles with Narcan.”

In Virginia, Chesterfield County Courthouse Gets A Narcan Vending Machine. For ABC8 News, Katelyn Harlow reports on the county’s new vending machine just outside the courthouse that dispenses “free Narcan, testing strips and other resources.” The county sheriff’s department explained to the news station that this resource is critical because “opioid overdoses can happen anywhere and Narcan could potentially help reverse them in minutes… we are giving people a second chance.”

In Washington State, Bellingham Expands Narcan Vending Machine Program. For The Bellingham Herald, Hannah Edelman reports on the city’s “ongoing effort to combat the opioid crisis” the city has installed two more “free 24/7 Narcan dispensers in a pair of city buildings. The expansion will continue this year with more vending machines being installed at the fire station and local food bank.